gipuzkoakultura.net

gipuzkoakultura.net

2026ko urtarrilak 8, osteguna

to enhance the condition and working of the iron, and the promotion of new factories on the Swedish model-met with the opposition of ironmongers and traditional operators. The Society's own initiatives, such as steel-working experiments of Aramburu in Arrasate-Mondragón and Zavalo in Bergara, a button factory (also in Bergara) and an attempt to create a tin and wire factory, failed abjectly without the direct support of enthusiastic collaborators.

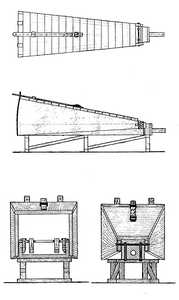

And because complete technical innovations were not introduced, as a result of the mistrust of the industry and the resistance to abandon old systems, competition from foreign imports continued to be a-sometimes insurmountable-stumbling-block. Protectionist measures were passed in the last third of the eighteenth century, intended to relieve the impact of foreign products on the local ironmonger's traditional markets (the Iberian peninsula and Spain's overseas possessions), but they came too late; as the members of the Sociedad themselves had remarked in 1768 "a quintal [a hundred pounds] of small hardware that they bring us is equivalent to fifty-one quintals that we mine and our extraction is left in naught". There were various reasons for this lack of competitiveness: the high unit cost of the product-in iron and charcoal-and low productivity, accentuated by the seasonal nature of the work. As a result, the building of new factories was complicated, while encouraging of the use of local coal-whose poor quality made it scarcely profitable-was even more difficult, despite the fact that the Society drew up exploitation programmes and economic incentives for raw materials, which did not receive adequate backing. As a result, the introduction of the fanderías marked no more than the first and most important step in the reorientation of the industry towards systems which were better suited to the new times. The first, not only in the Basque Country but in all of Spain, was the Rentería Fandería, built in 1771 by the Marquis of Iranda in the existing forge of Gabiriola or Renteriola. He installed innovative machinery which mechanically cut up the iron-which had first been heated in coal-burning reverbatory furnaces-and then used a series of cylinders to draw, widen or thin it as required. This considerably reduced the work involved in forging and processing and meant that the output no longer depended only on the skills and capacity of the operators. The factory mainly produced iron fittings, nails, rods and hoops Introduction of this new technology might have had an important impact had the War of the Convention and the resulting damage suffered by the Fandería not prevented it spreading to other areas. After the war, the works were used to prepare industrial flour, using the new Austro-Hungarian system.

The second mill of this kind the Iraeta Fandería in Zestoa, was founded by the Duke of Granada de Ega, and built on the site of the Iraeta Forge in or around 1774. It manufactured iron flasks for transporting mercury from mines in Latin America, and according to Madoz's account, by the mid nineteenth century, it was employing fifty operators.

In 1844 the Iraeta Fandería was radically altered when its contract to supply the state was suspended. It was re-founded as José Arambarri y Cía, and the product range was extended to include tin plate, in imitation of the processes used in England, Belgium and France. In 1855 it became the Vera-Iraeta Iron Factory, and its activities were extended to include mining in Vera de Bidasoa. The works were later used for the first natural cement plants in the Lower Urola area.

Another interesting case is the Anchor Factory in Hernani. In 1750, thanks to the intervention of the Marquis of La Ensenada, the forges of Fagollaga, Pikoaga and Ereñotzu won a contract to supply anchors for the Spanish Royal Navy. The only investment required was in making slight alterations to the traditional workshops and providing a place for deliveries and checking entries; no renovation of techniques or equipment was needed. The various setbacks suffered by the Spanish crown, however, brought and end to many of its private contracts, including the provisioning of anchors, and by the mid-nineteenth century the forges had been closed.