gipuzkoakultura.net

"...since both here and in Necaburu and Legazpia and in other places, we have hammer smithies and others using water hammers and manpower...". Some years earlier, King Alphonsus XI, signed the Forge Liberties (1328), a special set of laws for the forges of Oiartzun and surrounding areas. The document clearly proves that such forges existed and had probably been there for some time previously, stating:

"...these smiths, to make houses and forges and mills or wheels [...] make use [...] of the lands and the waters [...] as they used to do in the time of the kings before us".Between the end of the thirteenth century and the beginning of the fourteenth, therefore, the new system was successfully introduced in two ends of the province where there were good seams of iron ore: on the one hand Zerain, Zegama and Mutiloa, and on the other Arditurri and Peñas de Aia. These areas also lay near the clearest inroads of Navarrese influence; the San Adrián pass and the Bidasoa valley, respectively.

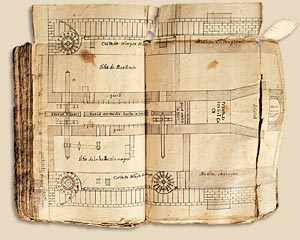

![27. Water wheels by Villareal de Berriz (1730, Second book of The Practise of Metallurgy of the [Second] Commissions of the Royal Basque Society of Friends of the Country).](../../../img/16/ruedashidrau.jpg)

Essentially a forge contains a dam or weir, to capture the water; a channel or millrace, to channel it, a millpond, a water tunnel-where the wheels are located-and the iron workshop itself. In addition to this basic set-up, there were other elements such as the furnace or area for preliminary roasting and calcining of the ore, the platform and perhaps small sheds where the ore was stored and cut up, etc.

The internal layout of the forge was quite distinctive. The hammer and hearth stood opposite each other. The hearth, an open furnace, which generally had no draught of any kind, was fitted into the hammer-wall. This construction divided the workshop into two spaces and acted as a fire wall, preventing the fire from spreading to the bellows which were located on the other side from the furnace. The charcoal and iron stores were linked to the workshop by two or three holes. In many cases the stores were loaded through hatches or simple apertures at a height, which took advantage of a natural slope, or along gangways.

A number of studies have been conducted into the working process of these forges, and there are also accounts from historians and travellers from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, setting out the basic practises and tasks involved in obtaining pig iron from the ore. A comparison of these accounts shows little change in the procedure during the development, high-point and decline of the forges.

carboneros whose main customers were the forges. Various types of iron

ore were available, but in all cases it contained a high carbonate content.

As a result, and probably more so than in Bizkaia (where there were more red

and bell hematites) the ore had to toasted or calcinated first. This operation

was carried out directly in ovens or bucket furnaces, like limekilns, remains

of which can still be seen at the Olaberria forge in Oiartzun. This combustion

process not only improved the quality of the ore, but also made it easier to

further cut up the ore and thus reduce the mass to be used in the smelting process.

The inner furnace of the forge was charged with alternate layers of charcoal and shredded ore, which was then set alight, and the fire was kindled with air from the bellows. When the mass of iron began to turn to a paste, it was stirred and any impurities and slag were drawn off through a hole. The mass was then removed using long rods and placed under the hammer, where it was beaten on the anvil to compact the particles of iron and charcoal and scatter and extract any remaining impurities.

The result was the raw iron known as tocho

, which was used to make semi-manufactured

elements such as ingots, hoops, billets, etc. These were then worked into shape

by the blacksmith.

In recent years, practical experiments have been conducted to recreate the work in these forges. In the Basque Country, the research carried out by the Arkeolan group has been particularly important, and has yielded interesting results at the reconstructed Agorregi forge in Aia.

The first great division of the industry appears to have developed as a result of specialisation: some forges devoted themselves to the work described above-working the ore to obtain metal-and were known as the Greater Forges [Ferrerías Mayores], as opposed to the Lesser Forges [Ferrerías Menores], which used the iron produced by the Greater Forges to make tools such as nails, hoes, ploughshares, spades, and so on.

An important feature of these forges was that they were operated on a seasonal basis. Because they used water-power, they were dependent on rainfall and the amount of water in the rivers. They generally worked from October to June, with some variations depending on the autumn and spring rainfall. During the unproductive months of summer, repairs were carried out on weirs, waterworks, buildings and machinery, and deals were struck to build up a store of raw materials or the winter months.

Occupations and operators.- Different writers give different accounts of the numbers of workers employed at each forge, ranging from just five or six to exceptional numbers of thirty or even a hundred. One explanation for this striking variation may be that whereas some writers only counted those working directly in the smelting and forging operations, others included indirectly employed workers. There was considerable labour specialisation in the forges: as well as the ironworkers themselves, other tradesmen were required for procuring the raw material (charcoal-makers, miners, cart-drivers); for manufacturing (armourers, cutlers, boilermakers, horse-shoers, etc.) and for marketing the products (journeymen, bookkeepers, traders, people involved in transport over land and sea, etc.).

Because of the seasonal nature of the work, it must initially have been common for one individual to perform various jobs. However, as the work became more specialised and the productivity of the forges increased, this practise gradually disappeared. A regular passive rental system for the premises-which the wealthier nobility had inherited from the early days of the industry-was gradually developed. Through the administrators and, later, by contract with individuals, whole iron-working enterprises were to be built up, associated with a master mill operator, who ran the works, and whose business might take in two or even three different forges.