gipuzkoakultura.net

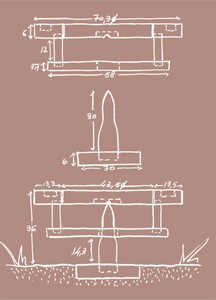

The wheels used in Eskoriatza and Zegama were similar to those employed by other potters in the Basque Country The modern version appears to have originated in the sixteenth century, either in Italy or in the Iberian peninsula. It consists of two wheels fitted to a shaft more than one metre high. The smaller wheel (or cabeceta) was about 30 cm in diameter, and the larger one (the volandera) was about 110 cm in diameter. The entire assembly was called an erroberie or wheel. When a particularly large-based vessel had to be made, a larger wheel was placed on the cabeceta, known as a sobrecabeceta. The potter moved the wheel by pushing the volandera with his foot.

Until the 1930s, these wheels were made entirely of wood except for the bottom tip of the shaft and the top of the shaft onto which the cabeceta was fitted. In some cases, however (in Uribarri Ganboa and Marañon, for example), boxwood was used for the tip of the shaft because of its high resistance to wear. This tip spun on a point in a metal plate that was fitted in a wooden block or in a stone. But we have also been told that it was common to use a copper coin, or even the base of a txikiteo glass [a very thick-based glass tumbler] instead of a plate.

From the 1930s on, certain innovations were introduced: a full iron shaft, metal cabecetas, metal hoops or rims of lead or iron attached to the volandera and-most importantly-the incorporation of a set of ball bearings in the base on which the axis rotated and in the part where it met the turntable.

Eventually, petrol engines and subsequently electric motors were introduced.

But in addition to these widely-used wheels, we also have evidence of two exceptional ones used in the Basque Country-in Gabriel Fernandez's pottery in the Torcachas district in San Andres de Biañez, Karrantza, and in the Cazaux family pottery, in the Négresse district of Biarritz.

Our only record of the Karrantza wheel is a description made by a person who saw the potter at work, and an account by his grandson. From the description, the wheel sounds similar to one we saw in Jose Vega Suarez's pottery in Faro, in the parish of Limanes, near Oviedo. Jose Perez Vidal describes it as, one of the oldest and simplest

of wheels, and he believes its origins can be traced back to the very first potter's wheels. The wheel protruded about 36 cm from the ground and the potter sat in front of it on a three-legged stool, rather like a milking stool. He moved the wheel by pushing it with his hand, which he inserted in some holes near the edge of the wheel. It would be interesting to know where the potter of Karrantza might have learnt of this arrangement.

The Cazaux family pottery is in some ways similar to those used in Brittany. It is 51 cm high. The potter sat on a board, with his legs open, resting his feet on two "stirrups", consisting of two boards protruding at right angles from the seat. As in the Breton wheel, he moved the large wheel using a stick.

The invention of the potter's wheel revolutionised earthenware manufacture and might be said to have industrialised the craft, allowing potters to create more and better pieces and cater to non-local markets.

Previously, clay vessels appear to have been made by women, but with the invention of the potter's wheel, the process became a man's job.

T.K. Derry and Trevor I. Williams in their "History of Technology", say that the potter's wheel was invented in or around 3000 BCE and that in its most rudimentary form, it rotated on a pivot fitted into a cleft in a rock. The oldest known wheel was discovered by archaeologist Leonard Wooley in 1930, in Ur. It dates from around 3250 B.C.E. and belongs to the Uruk period.

The potter's wheel was most likely introduced to the Iberian peninsula by the Phoenicians and Greeks and spread to the hinterland by Celts and Iberians. It first appeared in the Basque Country in the second Iron Age.

In the Intxausti workshop there were always two wheels. Essentially, they were identical to the others we have seen in the Basque Country. Only the larger of the two, which has a diameter of 112.5 cm, still remains. The hole through which the metal shaft passed measures 4 cm. and opens into an iron plate in the centre of the wheel. This wheel was never fitted with a metal rim or ball bearings. The bottom of the shaft rotated on a bronze bushing embedded in a block of stone. The shaft was fitted to the table by means of two metal hinges, which had to be oiled frequently. This is Gregorio's description of the process of throwing a jug:

Some pieces, such as large jars, had to be made in two parts. First the inside was turned to about half-way, leaving a kind of channel along the top edge which made it easier to attach it later to the top half. The two parts were attached the next day, when the clay was drier and the bottom section could bear the weight of the top.

The following were the tools normally used by the potter during the turning operation:

- The profile, described above.

- The comb, described above.

- Metal wire, with a stick at one end to hold it better. This was used for the same purpose as the reel of thread described above, but on larger pieces.

- Thread, described above.

- The casco, a type of unglazed cup slightly split vertically down the middle, which was used for turning cups.

- An L-shaped fettling knife. The longer arm was normally about 10 cm long and the shorter arm 4 cm long and 3 cm wide. Gregorio also used a Z-shaped fettling knife.This was the sequence of operations involved in fettling cups:

- Make a type of mould on the turntable, using the somewhat hardened clay, and then turn it with the fettling knife. The result was a semi-spherical mass of about the same volume as the inside of the cups to be fettled. Its function was to help fit the cups upside down on the turntable.

- Attach the cup to this mould, and, turning the lathe, apply the fettling knife to the base to remove clay and give it the required shape.

To decorate a piece they used half of a reel of thread, which they turned on a screw attached to a small stick with which they held it.

The reel had various notches in it, and these left a mark on the vessel as it was gently turned on the wheel.

The vessels were then glazed and enamelled to make them impermeable. More recently, they were first given an underglaze of engobe3 on top of which the glaze was applied.

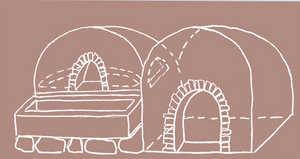

Enamel glaze, which gave the vessel a white tone was widely used in Zegama. It was prepared with tin, lead and sand in a small kiln called a padilla. This consisted of two adjoining chambers, one for the fire and the other for calcining the lead and tin. In Zegama, the firebox was 1.20 m. square and 1.30 m high. The ceiling was vaulted. The door for introducing the fuel was 0.60 metres in height and 0.44 metres wide.

The adjoining chamber, the calcining chamber, was circular, 1 metre diameter and had a vaulted ceiling 60 centimetres above the base. The base of this chamber stood 70 centimetres above the firebox. The door for introducing the lead and tin was 31 centimetres high and 28 centimetres wide. The base of this door stood 6 cm above the floor level of the chamber. In the wall between the two chambers there was a small vent 42 cm wide by 40 cm high, to draw the fire through.

According to Gregorio Aramendi, the kiln worked as follows: first the lead (which came from old pipes, etc.) was introduced in the calcining chamber. The fuel-normally furze-was then lit. The mouth of the calcining chamber acted as a flue, drawing the fire from the boiler into this chamber through a vent in the intermediary wall. It took one hour for a charge of 100 kg of lead to melt, after which 10 kg of tin in small bars was added. After a while a "type of cream" began to rise to the surface (Gregorio calls it calcine). This was removed and shovelled into a stone chest which stood in front of the door of the chamber. The iron shovel hung from a chain, secured to beam in the ceiling, so that it only had to be moved back and forth. After about two and a half hours after the first calcine was removed, the operation in the padilla kiln was complete. The entire operation lasted between three and four hours.

This calcine was then sifted, and any lumps were sent back to the padilla to be calcined again in the next operation.

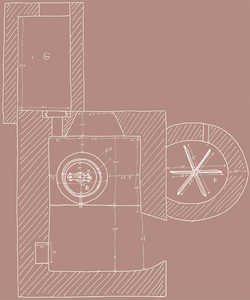

The calcined mass was then mixed with an equal amount of sand, which came from Nabarretejo in the province of Alava. The entire mixture was then ground. Before the introduction of the water mill, this process was carried out manually. The fixed bottom stone was shaped like a casserole dish and the top stone rotated in it. It was moved using a stick, the bottom end of which fitted into a hole close to the edge of the stone; while the top went into another hole in the ceiling to prevent it from skipping up and down too much. We have seen one of these bottom millstones in the pottery of "Aitamarren Zarra", now used as a seat. It has a total diameter of 63 cm and an external height of 24 cm. The hole is 37 cm in diameter and 17.5 cm deep. There is a small hole, 3 cm in diameter, to let the ground material out.

In the case of the water mill, the moving top stone measured 60 cm, and the bottom-or fixed-wheel, was slightly bigger. It was fitted into a cement bowl, the edges of which were fitted with small boards to raise the height and prevent the enamel from flying out during grinding. In the centre of the top stone there was a 16 cm hole, through which the shaft from the water wheel passed. The wheel was made of metal and had a diameter of 128 cm and a width of 23 cm. The water came from the River Oria, near the bridge close to the pottery, passing through a channel 40 metres long, to the tank (2m x 1m) next to the wall where the mill had a window. When the hatch of the tank was opened, the water fell on the twenty-five paddles of the water wheel, causing it to turn.

The tip of the shaft and the socket in which it turned were both made of bronze. The socket was fitted into a log, secured on either side with two stakes.

As the shaft rotated, it turned the top stone by means of an iron plate fitted with a square hole in the centre, at the ends of which there were iron bridges firmly secured near the edges of the stone. These bridges were 17.5 cm high and had a rod at the top, which ran into some holes in the plate. They were held in place by means of pins. The plate measured 48 cm long and 12.5 cm wide.

The top stone stood slightly to one side of the cement pan, so that the mass of the enamel would fall on the narrowest part and rebound into the centre, once again going in between the two stones through the central hole through which the shaft also passed.

Each batch contained 16 cups of calcine and some water. More water was added every two hours. It took about eight days to grind the calcine from a single batch from the padilla kiln-about 200 kg.

The milled enamel came out through a small pipe in the base. At this particular mill, a section rifle barrel was used for this purpose.

Gregorio Aramendi remembers that before it was mixed with the sand, the calcine used to be introduced into the combustion chamber of the large pottery kiln where it was re-fired. The chamber had a shelf (or "apal") running round the bottom for this purpose, on which the calcine was placed. After firing, the calcine was reduced to small stones, which had to be crushed in a mortar before being taken to the mill. The mortar in "Intxausti" consisted of an iron pot fitted to half a barrel. The pestle was made out of part of an old mortar shell.

The glazing or sealing was made with "leaf alcohol"-lead ore imported from Linares. It came in the form of stones, carried in baskets of about 50 kilograms each. First these stones were crushed in the mortar. Once the lead ore had been ground down, it was mixed in equal proportions with Murgisarri red clay and taken to the mill.

After the Spanish Civil War in 1936, lead ore began to be extracted in Zerain from mines which had first been worked by some Germans. Both the enamel and the glaze were applied to the vessels, when they were dry. In order to coat the inside of a vessel they would pour the enamel or glaze inside it and shake it until the surface was completely covered. Any surplus was then poured back into the bowl. To cover the outside, they turned the vessel upside down and held it in one hand, while they poured the glaze or enamel over it with a cup.

Latterly, the only decoration on the vessels was some type of incision. However, in the nineteenth century, tin-enamelled crockery at least was commonly decorated with green copper-oxide patterns, sometimes edged in brown. We have seen numerous examples of such pieces among the debris found near the "Aitamarren Zarra" pottery, and on a jug in the "El Castillo" restaurant in Beasain, which was made in Zegama. The rubble also shows that many vessels were also enamelled in white on the inside and had a lead glaze on the outside.

The chamber had two doors of the same dimensions, which-like the mouth of the hearth or combustion chamber-were built into the wall facing the Oria.

This kiln had a uralite lean-to roof, supported on walls 54 cm thick which rose above the walls of the kiln itself. The walls on the door side were 2.55 m high, while on the road side they were 1.2 m in height. In the middle of this roof there was a sliding plate which was opened when the kiln was lit, to let out smoke and fumes.

Gregorio Aramendi says that because it took several days to charge the kiln, they had to guard against sudden rain, which would have ruined any unfired vessels. We know that these roofs were also used in other kilns in the Basque Country, although they were usually much more makeshift.

Sixty centimetres from the threshold of the door, there were steps on either side if the kiln leading to a passage 90 cm wide (60 of stone wall plus 30 of brick shell), between the walls that supported the lean-to roof and the inside of the kiln.

As in the case of other kilns, the charge protruded about 50 cm above the top. The potters placed cups in this area, which were used as test pieces to ascertain the state of firing at any time.

The vessels were placed on horizontal boards (tacas) mounted using fired clay cylinders of different heights (bodoques), and bricks.

In Intxausti when the fuel used was gorse, which "lifted the fire up" to the top of the kiln, there were generally up to ten layers. When gorse was scarce and they had to use pine kindling, they only built six.

The vessels were placed upside down in the kiln and because of this the potters would normally remove the glaze or enamel around the rims with the palms of their hands. The cups, plates, bowls, etc. were separated during firing, to prevent the enamel from sticking, using trivets called txakurrek ("dogs"). The jugs were supported on floor tiles, called planchas, about 15 cm long and somewhat narrower than the mouth, to allow the heat in and ensure a bright glaze.

The holes in the centre of the base were surrounded with three bricks each, in order to dampen the force of the fire on the first pieces.

The firing process lasted between nine and ten hours. The two first firings were made with a gentle fire, in the mouth of the firebox to temper the kiln. The fire was then intensified and reduced again towards the end of the firing process.

Three days after the fire had been extinguished, the vessels were removed and the adobe walls which had covered the doors during firing were removed. Formerly the embers were drenched in water to be used as slack.

Three people were generally employed in the firing process.

- Cups (katilluek) in three sizes, of which the smallest were called kafekatillue (coffee cups). Most were enamelled in white on the inside only, but some also had enamel on the outside.

- Plates (platerak). Most were only enamelled on the inside.

- Jugs (pitxerrak). These came in six sizes ranging from 1/4 to 6 litres. The largest ones were used for water; the others for cider, wine, txakoli (local wine), etc. Most were completely bathed in white on the inside, and half enamelled on the outside; but some were completely enamelled inside and out. The perfect line separating the glaze or enamel from the clay on the outside is characteristic of Zegama vessels.

- Basins (barreñoak). In five sizes, the largest of which had a capacity of 25 litres. Larger bowls generally had handles. They were only glazed or enamelled on the inside.

- Jars. In different sizes, ranging up to 25 litres. Small and medium sized jars were enamelled in white on the inside and partially enamelled on the outside. The larger ones were decorated similarly, but in lead glaze.

- Pots. In 2, 1 and 1/2 litre sizes. Nearly all were completely bathed in white on the inside, and half enamelled on the outside. They were used to hold sugar, salt, honey, cayenne pepper, etc.

- Drinking troughs for pigeons, hens, etc.

- Butter jars, in 4 sizes with white enamel.

- Botijos (drinking jugs with spouts).

- Flower pots.

- Money boxes, called eltzetxuak in Tolosa and itxulapikoak in Zegama.

- "Trick" jugs, completely enamelled in white. This is a type of jug with a series of holes in the upper half. To drink from it, you need to know the "trick", which consists of covering one specific hole and drinking out of another. This type of jug is very common in other parts of Spain, and was probably introduced here by a potter from Valladolid, Miranda de Ebro, or elsewhere.

Zegama clay, like that of most potteries in the Basque Country, was not good for cooking and stewpots and casseroles were generally imported from Arrabal del Portillo (Valladolid). They were imported in the form of bisque, i.e. fired without a glaze, and in Zegama they were then enamelled in white on the inside and glazed on the outside. This type of vessel was also imported from Navas del Rey (Valladolid), Pereruela (Zamora) and latterly from Breda (Girona).

This particular pottery catered to a large market, centring on the Irun road. They sold their ware to shops in Beasain, Ordizia, Legorreta, Alegia, Tolosa, Irura, Billabona, Andoain, Lasarte, Urnieta, Hernani, Astigarraga, San Sebastian, Pasaia, Orereta, Herrera, Oiartzun, Irun, Hondarribia, Zaldibia, Lazkao and Ataun.

Shopkeepers from Zumarraga, Legazpi, Oñati, Azpeitia, Azkoitia, Zestoa, Zarautz, Orio, Usurbil, Aia, Idiazabal, Segura, Mutiloa, Zerain, Altsasu, Etxarri-Aranatz, Olazti and Ormaiztegi came to the pottery to buy vessels.

In addition, many people came from nearby areas to buy the vessels directly.

Half of the output of the pottery, however, went to Ordizia, Tolosa and San Sebastian. They sold to six shops in Tolosa, four in Ordizia, four in San Sebastian, three in Hernani, three in Irun, four in Orereta, one in Oiartzun and two in Idiazabal.

Formerly the vessels were transported in low-bedded carts, pulled by horses. More recently, this method was replaced by lorries. Before the goods were distributed, Gregorio Aramendi travelled from shop to shop, taking orders.

Ontzi lantegi horrek merkatu zabala hartzen zuen, eta ardatza Irungo errepidea zen. Beasain, Ordizia, Legorreta, Alegia, Tolosa, Irura, Billabona, Andoain, Lasarte, Urnieta, Hernani, Astigarraga, Donostia, Pasaia, Errenteria, Herrera, Oiartzun, Irun, Hondarribia, Zaldibia, Lazkao eta Ataungo dendetan saltzen zituzten ontziak.

Gregorio gave me a list of prices dating from 1936:

- Five-litre jug, 1.25 pesetas.

- Large dish, 70 centimos

- Medium-sized dish 50 centimos

- Small dish, 30 centimos

- Large cup, 50 centimos

- Medium-sized cup, 30 centimos

- Small cup, 20 centimos

- 25-litre jug, 8 pesetas

- 12-litre jug, 2 pesetas

- Butter jar, 3 pesetas

- 25-litre basin, 10 pesetas