gipuzkoakultura.net

One of the royal highways that linked this region to the neighbouring province of Alava-through the famous San Adrián tunnel-passed through Zegama. This was of great importance to the town: before the development of modern means of transport and communication, the fact of being beside the road meant in some way keeping abreast of affairs in the outside world. In many ways, the old road played a decisive part in the economic, social and cultural life of Zegama. It only began to lose its importance in 1780, with the opening of the Leintz-Galtzaga road, which was safer and more convenient.

Another important milestone for Zegama came with the construction of a railway between Irun and Altsasu. Work began simultaneously in Tolosa and San Sebastian on 22 June 1858, and was completed in 1864, attracting workers not only from other parts of Spain, but also from Italy, France, Belgium, Germany and other countries.

And it is precisely from this period that the first records relating to potters date, together with numerous other craftsmen: weavers, espadrille makers, blacksmiths, shoemakers, tailors, ironmongers, chocolate makers, confectioners, etc.

From information given to us by Gregorio Aramendi Arregi, the last potter in Zegama, and Martín Azurmendi, the son of a potter, we know that one of the potteries stood on the site now occupied by the Circulo Tradicionalista. Martín tells me that the pottery was demolished to make way for the new building in 1932.

Hor egon zen, Martinek dioenez, Azurmenditarren lantegia egun eskolak dauden lekura, Mazkiaran Etxeberri etxera eraman zuten arte.

He also tells me that the Azurmendis' workshop stood here until it was moved to a house called "Mazkearan Etxeberri", on the site now occupied by the town's school.

Another pottery was located in the beautiful "Aitamarren Zarra" house. Here Julián Braulio Arrizabalaga Arizgoiti lived and worked until his death in 1900, at the age of sixty-six. None of his descendants appears to have kept up the trade.

The Azurmendi family moved to this same pottery later. The first member of this family recorded as being a potter was Ascensio Azurmendi y Gorospe, born in 1812. Ascensio married Francisca Erostarbe y Ugarte, and was succeeded by his son Silvestre, while his brother, Emeterio, became an espadrille maker. Silvestre died quite young, at the age of forty-seven in 1884. He was married to Ignacia Aldasoro. According to his great grandson, Martín Azurmendi, Ascensio died a year later, as the result of a terrible beating he received in front of the parish church in Zegama at the hands of the "warrior priest", Santa Cruz, which left him badly wounded and with a permanent stoop.

Silvestre was succeeded by his sons Santiago and José Agapito Azurmendi Aldasoro, who stayed in "Mazkearan Etxeberri" until the house burned down at the end of the nineteenth century. Subsequently, Francisco Arregi offered the two work in his "Intxausti Zarra" pottery. Francisco Arregi was one of the first socialists in Gipuzkoa, while Santiago Azurmendi, who supported the conservative Carlist cause, became the president of the Circulo Tradicionalista. Martin tells me that although their opposing political views were not a cause of conflict between the two men, neither they were never close friends.

Later, Santiago abandoned the trade and joined Electra Aizkorri in Zegama. José Agapito then rented out the "Aitamarren Zarra" pottery to the son of the potter Julián Arrizabalaga, who worked there until 1932, when he in turn rented the house out to Agapito Oiarbide, a shepherd in Oltza. Agapito tells me that José Agapito moved to Calle Santa Bárbara, where he worked as a barber. He was also a magistrate. He died in 1954.

The third pottery was set up by José Luis Arregi Larrea, and stood on the banks of the River Oria, outside the urban nucleus. He built a house, workshop, kiln, etc., beside the house, called "Intxausti Zarra" [Old Intxausti]. José Luis Arregi, who was born in the Lartxaun farmstead in Zegama, died at the age of seventy-three in 1899. His was married to Manuela Landa, from Irun.

With José Luis Arregi worked his sons José Joaquín-who died aged 19 in 1887-and Francisco José who kept up the pottery later.

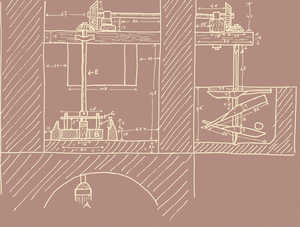

Francisco José Arregi was an enterprising man. He extended "Intxausti Berria" [New Intxausti], as the house built by his father was called, to fit large driers which were used not only for the pottery, but also for a tile-making workshop. He also set up a water mill near the workshop, for grinding varnishes and "blunging" or mixing the clay, using water from the river Oria. He bought Intxausti Zarra for six thousand pesetas and invested about the same amount in a complete renovation. He died aged seventy-two in 1929, and was succeeded by his son Francisco Manuel Arregi Guridi. Various people worked with the latter, including José Lorenzo Aramendi Arza, from Itsasondo, who was married to Arregi Guridi's sister, Micaela Josefa, and was the father of the last potter in Zegama, Gregorio Aramendi.

It was Gregorio who told us the names of some of the other potters who worked in Intxausti: Vitoriano Escudero, who was from Arrabal del Portillo, an important pottery town in Valladolid; Ponciano Ermingain Onaberri, better known as "Ponciano Tolosa", who was a potter until his death in 1944 at the age of forty-two and Martín Catalina Olmedo, also from Arrabal del Portillo.

Martiniano de la Calle, who worked for some time in Intxausti, also came from the same town.

In the mid nineteenth century there was a potter from Miranda de Ebro in Zegama, Juan González. He probably worked in "Aitamarren Zarra", as Braulio Arrizabalaga was godfather to one of his daughters.

Two types of clay were used in "Intxausti": the so-called "strong clay" (bustin gogorra)-also known as white clay (bustin zuria)-and red clay (bustin gorria). The red cay was dug on lands belonging to the pottery itself, on Mount Murgisarri, and also from common land, in "Errinea". Previously, it had been brought from "Altzibar", on land adjoining an old tile-making workshop. The white or hard clay was dug from land in front of the house, in an area called "Santa Agueda Aldea", which was also owned by the Arregis. The clay used to make the bricks that lined the kiln came from private land, in the Upper District of Zupitxueta.

In Gregorio Aramendi's grandfather day, a large amount of clay was brought from Zupitxueta to make roof-tiles and bricks. The "Aitamarren Zarra" pottery, which was owned by Agapito Azurmendi, got its clay from Murgisarri and the Arakamas district. Like the Intxausti pottery, they got clay for the fire bricks in the kiln from Zupitxueta. The best clay lay about 15 centimetres below the surface and picks were used to dig out the white or hard clay. For digging red clay, they used hoes.

They would generally dig the clay twice a year, normally in spring and in autumn, unless special needs arose.

The system of preparing the clay used in Zegama was the so-called "decanter" method. These decanters consisted of three holes dug in the earth on the banks of the Oria. The first was used to "blunge" the clay (mix it with water) with the help of wooden spades. Each batch consisted of five baskets of red clay, three of white clay and 20 pails of water. Once the mixture had obtained the consistency of "drinking chocolate", it was drained into the second hole through a channel with a sieve (galbaia), to prevent the sticks, pebbles, lumps of clay, and other particles from getting through. Once this second hole was full, the mixture was drained into the third one. Gregorio calls these pits "driers", although they are normally known as decanters. The sides were covered with a stone slab and they were considerably bigger than the blunging pit. The floor was of earth, covered in ashes to prevent it from sticking to the mixed clay. The clay was left in these holes for about two months, after which a layer about 60 cm thick formed. As the water reached the surface, it was drawn off through the gaps between the stones. The mass was cut into pieces with a sickle and then carried to the workshop. Sometimes the pieces broke up into different layers, corresponding to different batches (and thus different degrees of moisture), but if not they could weigh up to 40 kg each. The slabs were stored one on top of another, like a wall, in a damp place in the workshop.

The next operation consisted of spreading a layer of clay about 15 cm. thick on the ground, providing enough material for three days' work on the wheel. A little water was sprinkled on top and the clay was left for a while. It was then placed on a wooden table, called a sobadera (or kneading table), where it was beaten with an iron bar (previously it was common practise to stamp on the clay). After beating, the clay was "kneaded" like a piece of dough until it was elastic enough to be worked on the wheel. It was then cut into pieces (pellas or pellets), sized according to the vessels to be made, and turned on the wheel.

The amount of clay spread on the floor remained constant, since any material removed to the kneading table was replaced with fresh clay.

The blunging pit we saw was built by Gregorio's grandfather, when he built a water mill for milling varnishes. It was 120 cm wide and 85 cm deep. Once the right amount of clay and water had been placed in the hole, it was stirred using three metal blades attached to a shaft, driven-through various gears-by the water wheel (turtukoia), which was powered by the fast-running waters of the River Oria.