Freight launches and quechemarines

Basque freight launches were a product of the adaptation of

fishing launches for transport purposes.

For centuries, until they were supplanted by motor boats,

they retained the same essential features. The freight launch

had an internal space free of thwarts for stowing cargo. They

were also often of greater capacity, although they were manned

by a crew of about five.

In France, developments were introduced to the freight

launch, resulting in a type of boat known as the chassemarée

or quechemarín in Spanish (a two-masted lugger).

In the eighteenth century the quechemarín, which was initially

similar to the launch was gradually transformed into a

separate vessel, which could be used both for fishing and for

minor coastal traffic.

A local adaptation developed along the coast of Brittany and

Normandy was called bisquine; etymologically, the term

comes from the word biscayenne or Biscayan.

It is apparently similar to the cargo launch; however below

the waterline the sternpost is deeper, making the bow entrance

more vertical and thus improving sailing close to the wind. This

boat was later fitted with a mizzen and the tonnage was increased;

in this way it gradually evolved into an entirely separate vessel. © José Lopez

This cargo launch was built in the last period of sail power in

the Basque Country. The large sail area and the radical design were

a reaction to the threat of motor-driven ships.

Note the foresail, which is nearly as big as the mainsail. Both are

built “al sexto” and the mainsail, because of its size, is hauled in to

the foot of the mast to facilitate the manoeuvre. "Nuestra Señora de

la Concepción", one of three pleitxeruak (cargo ships) belonging to

Simón Berasaluze Arrieta. Copy of the oil painting painted in

Bayonne by G. Gréze, in 1878". Oil painting by Simón Berasaluze

Aginagalde. © José Lopez

Line drawing of a cargo launch. This nineteenth century cargo

launch, built by the Mutiozabal shipyard in Orio reflects some of

the common features of this type of vessel. The shallow draft and

water lines of the hull were similar to contemporary fishing launches,

and they also had fore and main sails. However the cargo

launches were larger, with a capacity of between twelve and sixty

tonnes. © José Lopez

The full shape of the hull of the quechemarín necessitated a

large sail area for sailing in gentle winds: mainsail and foresail with

its topsail, plus the jibs and the mizzen, which helped improve the

boat’s steerage with a bow wind, making the helmsman's task easier.

Sudden changes in weather in the Bay of Biscay make it essential

to be able to lower the sails quickly, so the boat is designed to

sail in a stiff breeze. If the wind gets up even more, the amount of

sail can be reduced to just the mainsail and the fore, in a rig that

is very typical of the chalupa. © José Lopez

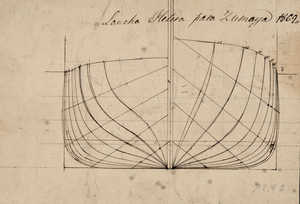

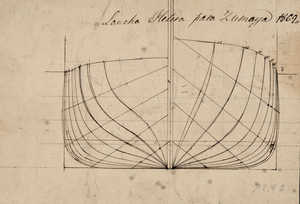

Rib frame of a freight skiff, Zumaia, 1869. The inherent instability

of any boat with a shallow draft was compensated for in the

flat-bottomed skiffs. At the same time, these shapes maximised the

cargo capacity. The shallow draft of these vessels required the use

of a side keel to reduce drift. © José Lopez

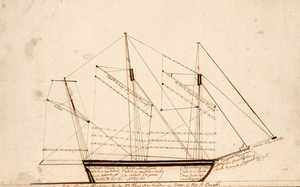

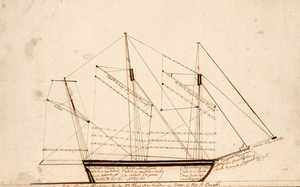

Plan of spars on a cachemarín (quechemarín). The picture

clear-ly shows the complexity of the spars and shrouds needed to

hold up the mast and its topmasts. We can also see the rows of

reefs used to reduce the surface of the lower sail, and a small

mizzen topsail. © José Lopez

The Granvillaise is a replica of one of the last bisquines. She

was built in 1990 in Granville, in the bay of Saint-Malo by the

Association des Vieux Agréements. Sailing trials have confirmed

the extraordinary nautical qualities of this type of ship, which is

particularly manoeuvrable. © José Lopez