gipuzkoakultura.net

The Romans' interest in Gipuzkoa may have been limited to its mineral resources, the troops and taxes it supplied and its strategic position on land and sea routes, but Roman rule brought substantial changes to the way of life of many local people, especially where urban lifestyles were adopted. Indeed, the city was the most important vehicle for transmitting Roman models: in it were concentrated the functions which allowed the new administrative network to prosper. Researchers agree that natives of the northern regions of Iberia who enlisted as legionnaires contributed to the development of urban life in their birthplaces when they returned after the mandatory twenty-five years of service. Bearing in mind the sizeable number of Vardul and Vascon soldiers amongst the troops stationed in Britannia and along the Rhine, it is quite possible that they played a leading role in consolidating urban environments in the area.

The application of the Roman urban model brought about changes in architecture, street-plans, economic activity and in the mentality of the people themselves.

In architecture, more extensive use was made of bricks and roof tiles, concrete and special mortars. New forms appeared, such as the vault and the arch. Improvements were made to timber construction, which was widely used, while stone was employed for important or emblematic buildings. There were also changes in the ironwork used in building (with the manufacture of new nails and bolts) and in methods of reinforcement and finishing. Labourers had to acquire the skills required for the new systems and suppliers of raw materials, traders and transporters were also needed.

Rectilinear street systems evolved around main roads, squares and other public areas and the concept of building lots was developed. The urban area was delimited by a fence or wall, which marked out a special area with its own privileges. Over time, it became necessary to fortify these symbolic limits against incursion and attack. A main roads passing through a town became its high street and was generally paved in stone. Outside the road also played a dynamic role, acting as a focus for the poorer quarters when the population grew too large to fit inside the city walls and as a reference point for building cemeteries. The forum, a rectangular open area flanked by buildings, was the main venue for public events and ceremonies, as well as acting as a market and meeting place.

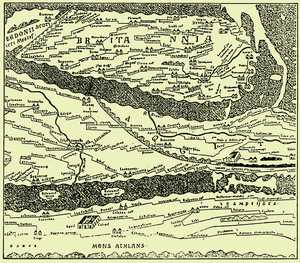

The road from Tarraco (Tarragona) runs through Ilerda (Lerida) and Osca (Huesca) as far as the last Vascon towns on the coast of the Ocean, both in the region of Pompelon (Pamplona) and Oiason, a city situated on the very edge of the Ocean. The road measures 2,400 stadii and ends at the border between Aquitania and Iberia. Strabo, Book III, 4.10. (written between 29 and 7 B.C.).

The River Magrada embraces Oeason. Pomponius Mela, Book III,1.15. 43-44 A.D.

The breadth of the Iberian Peninsula from Tarragona to the coast of Oiarso is 307,000 paces... starting at the Pyrenees and following the shore along the Ocean we come to the forest (or mountain pass) of the Vascons, Olarso. Pliny the Elder. Natural History, Book III, 3. 29 and 30. (middle of the first century A.D.).

Amongst the Vascons: the city of Oiassó and the Oiassó promontory (Coordinates: 15º 10', 45º 05'. 15º 10', 45º 50'). Ptolemy, Geographia, II.6. (middle of the second century A.D.).

Present-day Irun is an international communications centre, a bridgehead connecting the Iberian Peninsula to the continent of Europe. The main railway line from Madrid, the narrow-gauge line running along the Cantabrian coast, the N-1 and N-240 national primary roads (from Madrid and Tarragona respectively), the N-634 which extends as far as Galicia, and the A-8 motorway from Bilbao and Santander, all meet here to cross the Bidasoa River and pass through Hendaye en route north to Bordeaux and Paris, and east to Toulouse with its multiple connections with the Mediterranean and the Rhone corridor, Switzerland, Germany and Italy. It is the most important crossing-point in the western Pyrenees and a natural pass used by migrating birds. Irun is, also the successor to Oiasso, the Vascon civitas. This relationship is reflected in the name of the town (Iruña in Basque), like Pamplona (also Iruña) and the ancient city of Veleia, the third "Iruña" in the Basque Country. Irun-Iruña, together with the other Iliberris or Irunberris throughout Roman Hispania and Gaul (as far apart as Andalusia and Narbonne), was probably the generic term for an urban centre or city, to distinguish it from other population centres.

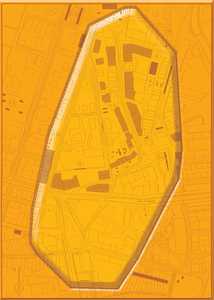

For many years Oiasso was thought to have been sited in modern-day Oiartzun, but the discoveries of the last thirty years have effectively put an end to this misnomer. Isolated discoveries were made in the 1960's at the Higer headland and Juncal Square, followed shortly afterwards by the discovery of the Roman cemetery at the chapel of Santa Elena. Years later, in the eighties, remains of Roman mining were identified in the surrounding area. In the early 1990s, evidence of the city itself were found - remains of the hot baths and residential buildings. As far as is known, the Roman civitas was situated on a height in the historical town centre in the area between the Town Hall and the end of Beraun. It was surrounded for the most part by the waters of the estuary, beside which a thriving port developed. Information gleaned from the excavations of the dock area in Santiago St and Tadeo Murgia St shows that the quays were built of timber, following the contour of the hillside in the area adjacent to the water. Ships could dock there at any tide and goods were unloaded and stored in quayside warehouses. Merchandise that had been spoiled during the voyage was thrown into the harbour alongside the jetty. Together with the dumping of urban waste in the same area, this practice finally rendered access to the quays by boat impossible. The urban settlement stretched over about fifteen hectares, presumably in a regular layout of streets, residential blocks, and public buildings and spaces. The cemetery, at one of the main exits from the city, extended beyond the city limits. The area of influence of the civitas stretched at least along both sides of the estuary up to the river-mouth, and remains dating from this period have been found within the walled part of Hondarribia, in the area of Ondarraitz Beach (Hendaye), on San Marcial Mountain, on Jaizkibel and at the foot of the castle of San Telmo in the Bay of Higer.

The inhabitants of Oiasso enjoyed a similar standard of living to that of other urban centres on the Atlantic; their diet, standards of hygiene, dress and leisure habits were all similar to those prescribed by Roman customs; they shared the same funeral rites and religious celebrations; they were familiar with written Latin; and they devoted themselves to trade and crafts, as well as mining, fishing and other pursuits related to the town's strategic position in the communications network. The remains of a bridge over the Bidasoa River have recently been discovered, confirming that this was a communications hub, linking Aquitania and Iberia, with all the traffic from the various highways and byways to the north and south converging at this bridge. The city was also an important port-of-call for coastal traffic between Burdigala (Bordeaux) and Santander. Oiasso's age of splendour lasted from 70 to 150 A.D.