gipuzkoakultura.net

Although contemporary references do not abound (Strabo, Pliny, Pomponius, Mela and Ptolemy are the most important) they do tell us the names of some of the most important settlements. The most prominent was the coastal polis (civitas or city) of Oiasso, in the dominions of the Vascons, which stood at the end of the Roman road leading from Tarraco (Tarragona). Further west, in Vardul territory, were the oppida (fortified areas) of Morogi, Menosca (next to the River Menlakou) and Vesperies, and the polis of Tritium Tuboricum. Beyond these, the River Deba marked the boundary between Varduls and Caristians. Of all these settlements the only one which has been positively identified is Oiasso in Irun, the Vascon tribe's only outlet to the sea from their lands which stretched back towards the Pyrenees. Any of the castros discovered in recent years might mark the site of one of the oppida, while the only evidence we have for the site of Tritium Tuboricum, which is thought to have been on the banks of the River Deba, is phonetic, linking it to the present-day town of Mutriku.

The juridical conventi - or administrative boundaries - of Clunia and Caesar Augusta met in Gipuzkoan territory. The notion of the conventus had existed since the time of Caesar, but it was defined and fixed during Claudius' reign. It comprised an administrative, political, juridical and religious unit. These conventi lost their raison d'être after the reforms of Diocletian about 288. Varduls and Caristians were governed by the conventus of Clunia (Coruña del Conde, Burgos), while the Vascons were included in the conventus of Caesar Augusta (Saragossa). Both formed part of the province of Tarraconensis, Augustus' new name for the former province of Hispania Citerior.

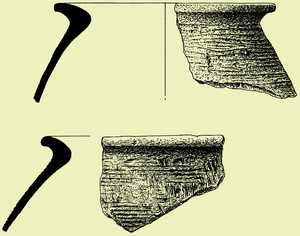

Archaeological evidence has added considerably to our information on Roman Gipuzkoa and in recent years a fair number of settlements have come to light. Excavations at the hill of Arbium, overlooking the inlet of Zarautz, show the existence of human occupation linked to the iron industry which developed in the fourth century and which was in some way related to the finds at Getaria belonging to an earlier age, which will be dealt with below. The town centre of Zarautz itself, where Roman coins and other remains have been discovered, was also inhabited during this era. Nearby, in the neighbourhood of Elkano, a new find has recently been made. Like the hill of Arbium, the hoards include no imported objects, evidencing an unsophisticated material culture. At the southern end of Gipuzkoa are the finds at Urbia and Leniz. In the former, several open-air constructions have been found, dating from the early imperial period (the first and second centuries) and related to herding practices in the area. Indeed, the valley of Urbia, which stands over 1,000 metres above sea level at the foot of the Aizkorri mountain range, is inhospitable for all but seasonal occupation.

The stone altar of Oltza, said to have been brought from Zalduendo to form part of the structure of a shepherd's dwelling, may well be related to the finds at Urbia and Leniz. It certainly appears clear that there was a connection between this area and the Plain of Alava, and specifically the city of Alba in San Román de San Millán. In the area in and around the watershed and close to the boundary with Alava Roman tanks have also been found, which would have been associated with the salt-springs of Leintz-Gatzaga. Although there are reports of an Iberian denarius coin being discovered in this area, the hoards found by archaeologists are not as old, dating from the fourth or fifth centuries and even later. From this same borderland area there are old reports of coins being unearthed at Idiazabal and Ataun, as well as a gold ring engraved with the imperial eagle found at the Jentilbaratza fort in Ataun (the ring was most likely a composite piece, with a stone cut in Roman times set in a mediaeval gold mounting). More recently, in 1986, a funerary inscription was discovered at the chapel of San Pedro de Zagama, alongside an ancient access route to the Aizkorri mountain range.

The fact that the evidence of cave-dwellings at Jentiletxeta II (Mutriku), Ermittia (Deba), Ekain IV (Deba), Amalda (Zestoa), Anton Koba (Oñati), Aitzgain (Oñati), Sastarri IV (Ataun) and Iruaxpe III (Aretxabaleta) dates from the fourth and fifth centuries, (i.e. the end of the period) is revealing. Cave occupation at this time is characteristic not only of Gipuzkoa but is frequently found in other regions, both nearby (Navarre, Alava, Bizkaia and La Rioja), and further afield. Such a widespread phenomenon has given rise to several theories: some hold that the caves were occasional shelters used in times of trouble; others that they were used by herdsmen or had some religious significance.

Roman objects are also being unearthed in town centres; first in Eskoriatza in 1982, and subsequently in Donostia-San Sebastián and Tolosa. Generally they are found outside their original context, forming part of deposits belonging to more modern periods of occupation.

By way of summary, the Roman remains discovered to date in Gipuzkoa have largely been found at the edges of the province. There is a concentration of remains along the coast of the Bay of Biscay, as a consequence of offshore traffic. Another point of concentration lies further south in the vicinity of the watershed connecting Gipuzkoa to the Plain of Alava and the Burunda Valley, through which the route from Pamplona to Briviesca passed. However, the greatest density is found in the Bidasoa Estuary round about the civitas of Oiasso. In any event, even on the basis of the evidence to hand, Gipuzkoa contained two polis and three oppida in addition to a considerable number of other settlements. This is a significant total: given the small size of the province and the likelihood of further finds in the future the picture to emerge is that of an unexceptional region of the empire. Only in one aspect is it unusual: the relative absence of epigraphs, only two of which have been found to date.