gipuzkoakultura.net

The discovery of the Altxerri cave and its prehistoric sanctuary was made in two very different phases. The existence of caves in the area was unknown until in 1956 a road was being built which passed in front of the Altxerri farmhouse. A temporary quarry was excavated to extract construction material from the limestone behind the farmhouse. One of the dynamite blasts blew open a hole one metre wide and 80 centimetres high, revealing a long wide gallery. Initially, the cave attracted no more interest than occasional visits from some young people from Orio and Zarautz, drawn to the cave out of a spirit of youthful adventure. Fortunately quarrying ended at this point as enough material had been obtained for the building of the road.

Six years later, the members of the Aranzadi Science Society – which had learnt of the discovery and the existence of chasms in the open gallery – decided to explore the cave. As they were making their preparations, they noticed some black marks on the wall close to the chasm, forming the figure of a bison. They subsequently discovered several other groups of figures in other parts of the cave.

They informed José Miguel de Barandiaran – then director of the Prehistory Department at the Aranzadi Science Society – of their findings. Barandiaran accompanied the discoverers to the cave, and authenticated the discovery.

However the presence of graffiti on some walls, left by the visitors of more recent years, made it necessary to proceed with caution with the study of the palaeolithic art. The first step was to install a gate to prevent access to the cave. Once this had been completed, the discovery was made public. The cave was named “Altxerri”, after the farmhouse standing next to it.

J. M. de Barandiaran made the first study of the figures, which was published in the magazine Munibe in 1964. Years later, in 1976, I published a second study of the figures with the collaboration of J. M. Apellániz, also in Munibe.

Barandiaran’s work also revealed the natural entrance to the cave, which lay close to the artificial opening created during quarrying and which was completely blocked with sediments and stalagmite mantles. This natural entrance has not been re-opened. Instead, we have preferred to preserve it as it was when we first arrived.

The cave contains both carvings and paintings. The former are in a good state of conservation, but the latter have deteriorated greatly over the millennia. The walls are very damp in many parts, and the result is that the paint has been smudged to the point where in many cases it is almost unrecognisable.

The cave has remained closed to the public since the archaeological discovery and this measure has been much more strictly observed than in Ekain, because of the fragility of the walls containing the figures. It is only open to prehistorians who can accredit their status with published works.

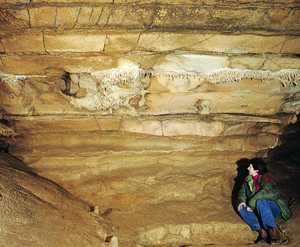

The present entrance to the cave opens in a nearly vertical cleft of rock, through well stratified limestones with numerous joints. These strata are relatively thin, with few exceeding forty centimetres in thickness. They are interspersed with other fine marly limestones – slatey in appearance – through which water seeps easily.

These strata have been greatly affected by the tertiary orogeny and there are some beautiful examples of folds and small joints, which often do not pass from one stratum to the next, since they are detained or restricted by the limits between them. As a result, a number of stone blocks have fallen and now litter the ground, especially near the entrance, making it very uneven. In other areas, sedimentation of the clay washed down by constant percolation of water has made the ground more regular.

As a result, the Altxerri cave is quite different to most others in the Basque Country, which often run through compact limestones.

The figures have been made either on the fronts or cuts in the strata or on the stratification planes. In the first case, the relative thinness of the strata made it necessary to make the figures quite small so that they would fit on these faces.

The first stretch of the cave is very wide, but it subsequently narrows into a long gallery, the floor of which is covered in fallen blocks of stone.

The first figures are located about one hundred metres from the entrance, in a narrow and elongated fork about eight metres long. The immense majority are carved figures.

The cave extends further in another gallery, which bends to the right. Here there are abundant paintings beside the carvings.

A little further on, the gallery forks. On one side it drops to a chasm of about ten metres in depth, which opens out onto other lower galleries. In the first stretch of the descending ramp there is another set of figures. Then comes the vertical drop to the chasm.

Initially, this drop was thought to mark the end of prehistoric man’s expeditions into this area of the cave, until two more figures were discovered at its base. This discovery, which was made subsequent to the publications cited above, sparked hopes that further artwork might be discovered in the magnificent lower galleries, since it was clear that early man had found a way of getting down to the bottom of the chasm. This hope was not fulfilled, however, and these two figures are the only ones in these galleries.

The way down to the chasm is covered by a relatively narrow bridge-like ceiling, which contains the figures located furthest from the entrance. Access to these figures is very difficult, and requires climbing a wall.

Altxerri is essentially a cave of bison - the animal most often represented. However, there is also a very varied range of other species, including not only hoofed mammals, (the favourites of the Magdalenian artists) but carnivores, birds, fish and even a serpentine shape.

As I have said, the first group of figures is located in a small side-cave and includes over fifty examples. We will examine some of the most striking ones.

The group begins with a symbol consisting of a deep and elongated incision, about 10 centimetres in length. On the left and right, a series of diagonal incisions meet the central one. These are shorter and shallower. This symbol acts as an introduction to the set of figures in the side-cave and the others in the cave.

A few metres further on, there is a panel of partially superimposed carvings. Particularly noticeable is a bison, with the back part deeply carved, a threadbare tail, two legs at either end and the line of the abdomen – the parts, in other words, where the animal’s hair is shortest. The front leg is made with a shallower cut. The rest of the animal is covered with an abundance of much finer, structured lines, which would appear to be an expressionist representation of the shaggy mass of hair that covers the bison’s forequarters, especially in winter. The figure seems to be saying: “a bison is a clearly defined rear, and after that... all hair”. For this reason, we call these stripes or scoring “fur scoring”.

An eye has been finely carved at the front of the scored part. A long horn emerges from the same area and continues outside the scored area.

Twenty-five centimetres above the hindquarters of the bison, there is another smaller bison, looking to the left.

Beneath the forequarters of the first bison there is an ibex facing to the left, with its head turned back. The carving of the hindquarters, short tail, back legs and ventral line is deep. The rest is very fine. On the abdomen there a deeply-carved area which may represent the typical dark patch on these animals.

To the right of this group, we can see the front part of a magnificent reindeer, made with deep cuts. This may represent an animal starting to stand up from a sitting position.

The head has been depicted with great care. Between the eye and the area of the nose there are a series of fine cuts, like those frequently seen in similar art mobilier representations of this animal. The front part of the flattened horn, the short ears, the rounded muzzle and the tuft of hair between the throat and chest put identification of the animal beyond all doubt.

The legs are very carefully carved. The knees (more correctly termed “wrists”) and the ends, with hoof and fetlocks can be identified.

Inside the neck region of the reindeer, there is a carving of a fox. The animal is almost complete and has been deeply carved using a burin. The ears are relatively short, and this, together with the presence of the reindeer, may suggest that this is an Arctic species which no longer inhabits the region.

The incision of the line of the reindeer’s neck cuts through the incision of the fox’s leg, suggesting that the fox was probably carved before the reindeer.

To the right of this panel, two flat fish are depicted on a fish-shaped rock. The top one of the two – which is positioned vertically with its head down – is complete and has been made with a deep carving, which becomes gentler in the longitudinal fins extending from the animal’s back and abdomen. At the other end the caudal fin can clearly be made out. Between the two runs the side line. This is a flat fish, similar to a plaice, dory or sole. The specimen from Altxerri is most similar to a plaice. This identification is further supported by the fact that the plaice is the most coastal of the species, and can be found not only in the briny area of rivers, but even further inland. Plaice can still be found today in the river running below the cave.

In front of this figure, there is the unfinished outline of a flat fish. The zoological classification may be the same.

Barrenerago sartuz, eta gorago, grabatu sakonez egindako bi irudi daude. Lehenak animalia baten burua, lepoa eta gorputz-enborraren hasiera erakusten digu. Marraztua du begia, eta marra lapran batzuek lepoaren azpialdea itxuratzen dute.

Even further into the niche and in a higher position, there are two deeply-carved figures. The first represents the head, neck and beginning of the torso of an animal. The eye is shown as well as a series of slanting strokes modelling the throat.

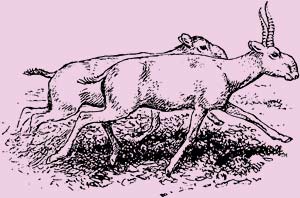

This animal most closely resembles a male saiga (females have no horns) in its typical vertical jumping position. The shape of the short unbranching and semi-vertical horns, excludes the possibility of cervidae, bison, urus, ibexes and chamois. The only remaining horned animal from the Würm period is the saiga antelope. In addition, the convex profile of the muzzle is identical to that of the saiga.

To the right there is the simpler carved outline of a second saiga. Only the profile of the brow and nose and the horn are shown. On its own, this figure would be difficult to identify, but comparison with the other figure suggests that it belongs to the same species. The brow and nose profile is closest to that of the saiga, and it is from this part that the horn grows, another feature of the saiga.

The intense scoring below the saigas represents a bison in a vertical position with its head down and its back facing to the left.

Next to these figures, but further into the niche, there is another carved bison. It faces to the left and is complete and very detailed. The edge of the rock has been used for the brow-nasal profile. The head has been completed with the end of the muzzle and the nasal orifice, eye and horn.

The right-hand wall of the niche or side-cave contains the following figures:

A male ibex facing right. The horns – much larger in males than females – clearly show that this is a Pyrenean and not an Alpine ibex, suggesting that these two species were already well differentiated in this period. The horns of the Alpine species form a simple arc, with the curvature on a single plane. In the Pyrenean species, in contrast, the horns first rise vertically and then separate from each other continuing on upwards. The front legs, reduced to simple appendices, are tucked together in a jumping position.

Twenty centimetres to the right of the ibex is the vertical figure of a fish, facing upwards, which appears to be similar to a gilthead. Supporting this identification are the head with its large eye, the long dorsal fins and the long narrow base of the tail. This species often enters river estuaries.

Further down, in the same area, the torso and lower part of a headless anthropoid have been carved. From an intermediate area between the chest and abdomen a long limb extends. It is placed too low to be an arm and too high to be a hypertrophied penis, although the glans-type shape at the end is reminiscent of one. On the lower back, there is an inlayed disc, made up of two concentric circles, with a series of lines extending from the outer circle. This may represent a sphincter with hair.

Near the gilthead, but on another rock plane, is the carved figure of a bison facing down, displaying its left flank. The animal is almost complete and drawn side on and in a walking pose, to judge by the position of its front legs. The tail is raised and arched forward. The sex is again well marked.

Above the animal are two vertical lines, one over the back of the hump and the other on the hindquarters, meeting it at the other end at the tip of the tail. At the point where the front line meets the body, there is a paint stroke, as if to depict blood flowing from the wound caused by the weapon.

Near the previous figures, on the hindquarters of a bison not described in this work there is a bird, whose back, head and neck are formed by a natural edge in the rock. The shape of this rock edge must have reminded the palaeolithic artist of the image of a bird. He completed the figure by carving the eye, chest and abdomen, the hind part of the back and the tail. The tail has various parallel incisions representing the feathers. The “art trouvé” quality of the representation is clear. No further specific identification can be made. The carving is deep in the eye and chest and of medium depth in the rest. This “art trouvé” style is well represented in Ekain.

Coming out of the side-cave containing the figures we have described, the main gallery turns right and 12 metres further on, in an intermediary area, there are further sets of figures.

Here, unlike the side-cave, paintings predominate over carvings. Unfortunately, some of the figures have been painted on a very damp part of the rock and the paint has been greatly smudged. It is just possible to make out a few paint marks, and it is scarcely possible to identify the animals in question. Any photography of the paintings is practically impossible.

One of the most striking figures is a bison. The head and front section of the hump have been preserved, as well as the hindquarters and the tail. The entire central area has been covered by a stalagmite.

On the right-hand wall of the same gallery, high up, overlooking the gallery, there is a painted and carved bison which occupies the front of one of the strata. The painting of the back legs cannot be made out as clearly as the rest the animal. The painting gracefully reproduces the line of the back and abdomen, the hind quarters with the tail and the back legs, one ahead of the other. The genitals are also shown. The technique used, where carving sometimes accompanies the painting, sometimes completes it and sometimes takes over from it, is different to the figures we have seen till now.

In order to gain access to the groups of figures furthest from the entrance, it is necessary to climb a stalagmitic mantle, pass under a small arch formed by the same concretion and position oneself on a narrow bridge between two chasms. One of the groups is on the north wall and the other on the south wall. The latter is made up of stratification planes, whilst the former is formed by the narrow fronts of the strata. It is on one of these fronts that most of the figures are found: seven bison, a horse, a chamois, an ibex and a probable urus, as well as some scored fields and symbols. Let us now take a closer look at some of these.

In the archway on the way to the figures, on one of the stratum faces, there is a bison, which has been painted and carved and which also makes use of the edges and cracks in the rock. The animal has in fact been created using features of the rock, which have been completed. The upper edge of the stratum acts as the back. One joint in the stratum serves as the rump and the base of one of the back legs. Other cracks complete the leg to the front and mark the line of the thigh in the abdomen. Another joint marks the scapular area and the base of the front leg. Between the front and back legs the line of the abdomen has been drawn.

We can see that the Palaeolithic artist saw animals in many of the features of the cave; animals flowing from the rocks in the depths of the caves.

Another stratum front forms a frieze of figures, separated by joints. The most conspicuous are a probable chamois and three bison.

The chamois stands in a scored field which extends beyond the figure. The paint covers almost all of the outline of the animal and models the inside of the head and torso.

In the same frieze and in the same scored field, separated by a joint, there is the painted figure of a bison, which is also largely covered by the scored stripes. The animal is facing to the left, towards another bison. These animal are as large as the thickness of the stratum will allow.

Behind this bison and following it, there is another painted and carved bison, of a similar size. The head, back, hind quarters, abdomen hair and front leg are partially depicted.

In a white calcareous concretion niche, from whose edge hang some stalactites, a horse has been painted on the frieze containing the bison and the chamois. The paint has gone from the back of the animal, but remains – in better or worse condition – on the rest. The figure includes no carving. The white colouring of the concretion may have made it unnecessary to “bleach” the rock, an effect produced in other areas with scoring.

Opposite this group there is another, located on the surface of stratification planes, instead of on the fronts of the strata. It contains four reindeers, four bison, a serpent shape and some other symbols.

The entire wall is very damp and the paint has almost completely vanished. The carving, however, is better preserved.

Particularly noticeable is an almost complete reindeer. The details depicted make it unmistakable: the general bearing, the muzzle, the horn, the hairiness of the chest, the line of the torso etc.

On the neck of this reindeer there is a serpent shape, winding upwards. The torso is formed by two parallel lines, over which is superimposed at the top, an angle which might complete the head.

Further down and to the right, on another stratification plane, just on the edge where the drop to one of the chasms begins, there is a beautiful painted figure of a bison, which makes very good use of the rock.

Finally, in the drop to the chasm itself, we find the last group of figures. These make use of a wide and practically flat stratification plane. The most important figures here are a deer and a bison.

The front of the deer has been painted and the bison is complete.

Two others bison, at the base of the chasm, complete the set of figures in this cave.