BASQUE CORSAIRS

Notes

Gipuzkoa has long lived in ignorance of the epopee which many of its ancestors lived along the coast and on the seas, an epopee widely written about by the few descendents of that legion of navigators, fishermen, shipowners and corsairs whose main roles in that period of powerful action came to an end so long ago.It was enough to let the three last centuries of history pass in silence to almost totally erase Basque signs of identity from the details of sea life.

With respect to Basque corsairs, this silence is understandable, partly due to the obscurity surrounding many of them. The reason for this –according to Michel Iriart- lies in the custom which many shipowners had of burning all the documents related to those who often made them rich. On the other hand, many corsairs only stood out on one single voyage or crossing and this unique piece of information was not enough to find out more about their origins, life and previous and future campaigns.

35. Basque Sailor. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

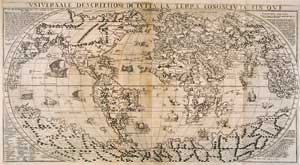

36. Map of the world by Antonio Lafredi (1580).

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

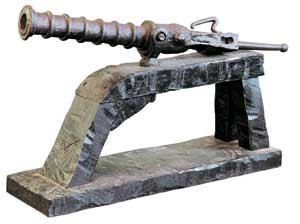

37.Small cannon.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

We must point that corsairs did not arise from a vocation for theft, but for the sea, since fishing was initially their main activity. Born between the mountains and the sea, the latter was so near that many made their lives on it, fishing and trading. Later they armed themselves in defence against the threat of foreign pirates and, only then, started pirating for themselves.

So, more than fishing and trading, corsairs spent more time stealing. "Letters of marque", that is, the permission which the king gave his seafaring subjects to go after enemies of the Crown until gaining control of the goods they were carrying had a lot to do with this. One King would give a corsair licence to steal and another would hang him for the same thing.

The concession of this permission differentiated corsairs from pirates. The corsair received a letter of marque from royal or government authorities to make war against another nation or to interrupt its commercial traffic. The pirate was a thief who also stole at sea, but with no permission whatsoever.

So, more than fishing and trading, corsairs spent more time stealing. "Letters of marque", that is, the permission which the king gave his seafaring subjects to go after enemies of the Crown until gaining control of the goods they were carrying had a lot to do with this. One King would give a corsair licence to steal and another would hang him for the same thing.

The concession of this permission differentiated corsairs from pirates. The corsair received a letter of marque from royal or government authorities to make war against another nation or to interrupt its commercial traffic. The pirate was a thief who also stole at sea, but with no permission whatsoever.

Letters of marque

Followed by England, France introduced corsair piracy during the first quarter of the 16th century –with permission from the King- against Spanish traffic to the Indies, ignoring the papal bulls and prohibitions of the Council of the Indies and the "Casa de Contratación" (an organism created by the Catholic Kings to regulate commercial traffic with America) in order to fight against Spain’s monopoly of certain colonies rich in silver.The Spanish King’s desire to prevent robbery and upset their enemy’s trade found a useful manner of doing so, by giving a licence for the assault and robbery of hostil ships to the brave and experienced seamen who inhabited the villages along the Basque coast. The Crown would protect them on the condition that they harass the enemy ships, meaning that the Basques took to this profitable employment, especially outside whaling time.

The first letters of marque were not granted to the Basque-French until 1528, although it must be said that the inhabitants of Labourd worked as anything that came their way: corsairs, pirates, filibusters and buccaneers. With respect to our provinces, we have testimonies from the end of the 15th century, such as the warrants issued in 1497 and 1498 by Fernand the Catholic, permitting privateering to be carried out by Gipuzkoans and Biscayans with no restrictions whatsoever.

38. Dukedom of Navarra and France, 1733. Eight real coins from the reign of Charles III, 1796, 1800 and 1807. An eight real coin from the reign of Ferdinand VII, 1822. Coin from the reign of Henry II of Navarra, 1587. One real from the reign of Ferdinand I of Navarra, 1513?. Two reals from the reign of Philip V, 1721.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

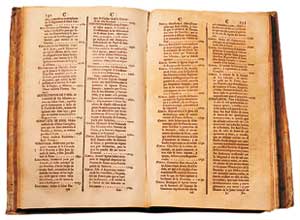

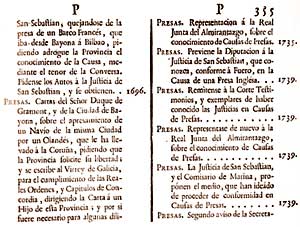

39. Extract from the book, "El guipuzcoano instruido". Donostia-San Sebastián, 1780.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

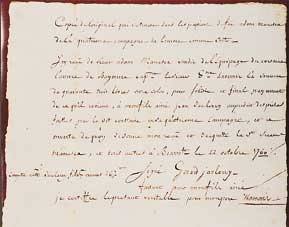

Let’s take a look at a letter of marque, a perfect example of which is that of the frigate "Nuestra Señora del Rosario", built in the 17th century in Donostia-San Sebastian.

"By virtue of the present document, the said captain, Pedro de Ezábal, in accordance with the Corsair Regulations of 29th December 1621 and 12th September 1624, can start privateering with the said frigate against people of war, to acquire the necessary arms and ammunition, and sail along the coasts of Spain, Barbary and France, fighting and capturing any ships of French nationality they find, due to the war declared with that Crown; any other Turkish and Arab corsairs they can find; and any other ships belonging to enemies of my Royal Crown, under the condition and declaration that they cannot, under any circumstances, go to nor pass the coasts of Brasil, the Terceira, Madeira and Canary islands, nor the coasts of the Indies...

Issued in Madrid, on 28th August, 1690. I, the King".

Issued in Madrid, on 28th August, 1690. I, the King".

40. Sharing out of booty on a corsair boat.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

41. The building presently housing the Untzi Museum in Donostia-San Sebastian, was used as a guild and prison by the Consulate of Donostia-San Sebastian.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

The corsairs would give the captured goods to the authorities, Royal Justice or governors of the province.

However, some corsairs continued to steal, sometimes without waiting for the royal bull, and others when the letter of marque was out of date, and even in times of peace between Spain and its enemies. These corsairs were normally not tolerated by convention and would earn the name of "pirates".

Especially in Gipuzkoa, letters of marque were first transmitted by the Donostia-San Sebastian mayor’s office itself, until the Consulate took legal charge of the affair years later, and both would judge the legitimacy of each capture entering the port. Later, the Royal Privateering Regulations stated how the loot was to be shared out. According to these rules, artillery and prisoners went to the Royal Justice, while the boat and its merchandise went to the corsair’s family, where it was proportionally shared out between the shipowners, captain and crewmen, according to the amount of time which each one had been on the ship.

However, some corsairs continued to steal, sometimes without waiting for the royal bull, and others when the letter of marque was out of date, and even in times of peace between Spain and its enemies. These corsairs were normally not tolerated by convention and would earn the name of "pirates".

Especially in Gipuzkoa, letters of marque were first transmitted by the Donostia-San Sebastian mayor’s office itself, until the Consulate took legal charge of the affair years later, and both would judge the legitimacy of each capture entering the port. Later, the Royal Privateering Regulations stated how the loot was to be shared out. According to these rules, artillery and prisoners went to the Royal Justice, while the boat and its merchandise went to the corsair’s family, where it was proportionally shared out between the shipowners, captain and crewmen, according to the amount of time which each one had been on the ship.

Where and how they acted

The mens’ skill, captains’ decision and crews’ greed, including that of the shipowners, were conditions that abounded on these ships for privateering and piracy.Once established as such, the number of Basque corsairs increased rapidly all along the Basque coast, and the range of their activities grew in proportion.

The main bases of the Gipuzkoa corsairs were Donostia-San Sebastian, Pasaia and Hondarribia, and their range of activities spread as far as the English Channel. Later this range grew wider towards the north of Europe, the coasts of America and Barbary, in the north of Africa. Corsair ships were private property and were chartered by their owners. They were normally chosen for their speed and shallow depth.

Their main method of combat was by boarding, combined with the use of artillery. However, they were not normally heavily armed since they trusted in their victories by boarding, so that the ships they caught would suffer little damage, since they then had to sell them. They normally preferred marauding to stalking that is, navigating in search of victims instead of waiting for them at a certain point, although they would combine the two tactics..

42. Pasaia, between Donostia-San Sebastian and Hondarribia, was one of the main bases for Gipuzkoan corsairs.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

43. Extract from the book, "El guipuzcoano instruido". Donostia-San Sebastian, 1780.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

At other times they would wait in the port until information reached them about enemy merchants. Corsairs mainly dailed alone, sometimes in pairs and occasionally, when the enemy was strong, in larger groups or small fleets, where the fair sharing of prisoners became difficult and was less profitable.

With respect to prisoners, they would sometimes pretend to be whale hunting and catch English and French fishing boats; at others, they would take command of the merchants’ holds loaded with wine, cloth, silk, tar and resin. The attacked ships would consequently form convoys to defend themselves and obliged the corsairs to organize a multitude of plans in order to take charge of them. Ransom was also a form of loot, that is, the exchange of the prisoners taken by corsairs for money or, on occasions, the exchange of these prisoners for certain others.

With respect to prisoners, they would sometimes pretend to be whale hunting and catch English and French fishing boats; at others, they would take command of the merchants’ holds loaded with wine, cloth, silk, tar and resin. The attacked ships would consequently form convoys to defend themselves and obliged the corsairs to organize a multitude of plans in order to take charge of them. Ransom was also a form of loot, that is, the exchange of the prisoners taken by corsairs for money or, on occasions, the exchange of these prisoners for certain others.

44. English spark gun from the 18th century.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

45. Block and tackle. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

Finally, we have to underline the importance of privateering, especially with respect to our coasts, taking into account the number of corsairs that existed.

It would seem that the crews on privateering ships were extremely numerous. In the Gulf of Biscay, and during the 17th century, the golden century of Basque privateering, crews on corsarir ships were proportionally higher than those on ships belonging to the Royal Fleet.

These numbers reduced on expeditions to further-off destinations due to the need for more provisions.

Privateering, therefore, required a great number of crew members and the Basque population wasn’t large enough to fulfill this need, meaninig that they resorted to recruiting. Active corsair ships, although great in number, were limited and only went out when ships came back from the sea with other crews on board.

It would seem that the crews on privateering ships were extremely numerous. In the Gulf of Biscay, and during the 17th century, the golden century of Basque privateering, crews on corsarir ships were proportionally higher than those on ships belonging to the Royal Fleet.

These numbers reduced on expeditions to further-off destinations due to the need for more provisions.

Privateering, therefore, required a great number of crew members and the Basque population wasn’t large enough to fulfill this need, meaninig that they resorted to recruiting. Active corsair ships, although great in number, were limited and only went out when ships came back from the sea with other crews on board.

46. All aboard!. Drawing by Tillac.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

47. 16th-17th centuries.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia