THE EARLY STAGES

The Basques and the sea

There is not doubt that the Basques are one of the few peoples to have engendered individuals who, due to their love of adventure or enterprising nature, didn’t think twice about travelling further abroad than the horizons surrounding them. In spite of the affection they felt for their country, the Basques left home through necessity and due to their taste for adventure, helped by the fact that the sea was so near to them.With time, and uniting these motives, this part of the Cantabrian coast gave birth to excellent examples of corsairs and pirates who started plying the same seas as their ancestors had sailed on since ancient times, gradually coming to know and, in as far as possible, dominate it. Bur we mustn’t forget that privateering and piracy are as old as trade itself, and that they are closely related to maritime traffic.

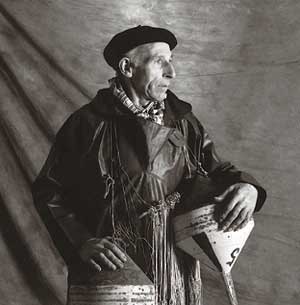

8. Basque Sailor. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

9. The waters of the Cantabrian Sea have been well known and controlled by Guipuzcoan sailors since ancient times.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Traditional tales about the voyages made by Basque sailors and their relations with the north are vast. Mairin Mitchell tells us of the legend which says that the first king of Kerry, in Ireland, was Eber, who came from the north of the Iberian Peninsula. At the end of the Middle Ages, it was accepted that Juan Zuria, the first lord of Biscay, was the grandson of a certain Scottish king, the son of a woman banished from her land by her father.

As Julio Caro Baroja says, this could never be accepted as true in a society with no great seafaring tradition. Nor, without a great seafaring tradition, would Basque seamen have reached Glasgow ant the Orkney Islands on their way north.

But, just as the Basques opened a way for themselves, it became increasingly necessary to defend the land and the sea. The 11th and 12th centuries were deeply troubled and it was during this era that the vikings and Norsemen appeared, the first plunderers to have come as far down as the Basque-French coasts.

As Julio Caro Baroja says, this could never be accepted as true in a society with no great seafaring tradition. Nor, without a great seafaring tradition, would Basque seamen have reached Glasgow ant the Orkney Islands on their way north.

But, just as the Basques opened a way for themselves, it became increasingly necessary to defend the land and the sea. The 11th and 12th centuries were deeply troubled and it was during this era that the vikings and Norsemen appeared, the first plunderers to have come as far down as the Basque-French coasts.

10. Engraving depicting a fishing scene in a house in Orio. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

11. Prow of the Oseberg boat. Oslo. The Vikings, from Scandinavia, appeared out of the mist, plundering cities such as Worms, Paris, Aguisgran, Maguncia, Lisbon... They would take their victims by surprise. The appearance of the sails of their Drakkar boats on the horizon would fill the inhabitants of the coast with terror.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

The Basque coast from Castro Urdiales to Bayonne has many sheltered bays and it was precisely in those found around Bayonne and in the port itself that the first pirates who arrived our coasts chose to settle. Bayonne was then, and until the second half of the 11th century, an important area which attracted these pirates, since it was a seaport with a great number of merchants and fishermen, as well as being an episcopal see and meeting point between Aquitaine, Gipuzkoa and Navarra. In fact, the evangelist and founder of the episcopal see, Saint Leon, was decapitated there by Norman pirates in the 9th century.

The Norman threat and these pirate appearances made the Kings realize the importance of defending their own coasts. So, at the beginning of the 9th century, these shelters or ports started receiving their official authorization in the form of "fueros" (provincial prileges granted by the King) with which they founded towns that, as well as for self-defence, served as the point of departure for merchandise in a period of Castilian commercial boom.

The Norman threat and these pirate appearances made the Kings realize the importance of defending their own coasts. So, at the beginning of the 9th century, these shelters or ports started receiving their official authorization in the form of "fueros" (provincial prileges granted by the King) with which they founded towns that, as well as for self-defence, served as the point of departure for merchandise in a period of Castilian commercial boom.

12. Imprint of the Hondarribia seal.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

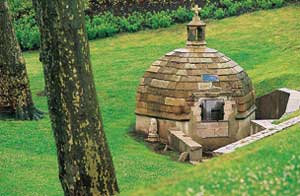

13. In Bayonne, tradition marks the place where, in 892, and on having been decapitated by Norman pirates, the body of Saint Leon fell after having covered a few hundred metres with his head in his hands. A fountain appeared on the said spot.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

The towns

The oldest "fuero" in the country is that of Bermeo, founded in 1082. Gipuzkoan foundations of the time took place as follows: Donostia-San Sebastian, prior to 1180; Hondarribia, 1204; Getaria and Motrico, 1209; and Zarauz, 1237. Later, the following towns were founded: Villanueva de Oiarso, 1230; Monreal de Deva, 1346; Villagrana de Zumaya, 1347; Belmonte de Usurbil, 1371; and San Nicolás de Orio, 1379.The economic momentum which these foundations produced were already obvious in the 12th century, when Gipuzkoa and Biscay started to take on important economic significance, with their great contingent of sailors and fishermen.

Concentrating ourselves on Donostia-San Sebastian, this was the first "fuero" in the peninsula to have maritime regulations, since it meant the creation of a real maritime code, which was later applied to all the Gipuzkoan municipalities. Thanks to the "fuero", the port of Donostia-San Sebastian became the natural outlet for products from Castile, which, with time, became a great exporter, especially of wool. The marked commercial character which Donostia-San Sebastian was acquiring, and subsequent prosperity, brought pirates and corsairs, always lovers of other people’s belongings, to our coasts.

14. The seal and shield of Donostia-San Sebastian do not show a fishing boat as do those of Getaria or Hondarribia, but a commercial ship, due to the mercantile character which the town adopted from its early stages. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

15. The coast between Zarautz and Getaria..

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Far from our coasts

The Basque seamen paraded themselves over all the known seas, and some of them were not only merchants. In 1282, a body of Basque volunteers took active part in the conquest of Wales, together with the Anglo-Norman army. As stated by a Genovese chronicler in 1304,..."people from the Gulf of Gascoyne crossed the straight (of Gibraltar), with vessels called "cogs" and went privateering against our ships, causing not a little damage".In the Early Middle Ages, the Basques acted as transporters for Italian merchants and set up communications between the Mediterranean and other areas in the North of Europe. When the Catalonians needed sea-going vessels, they would normally look for them in the northern ports, such as the Basque Country. This means that it was the Basques who made them, crewed them and, as was customary at the time, rented them out to Kings and foreigners.

Moving from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, Basque seamen were also sighted in 1393, reconnoitering around the Canary Islands or, later, navigating in expeditions to the Gulf of Guinea.

On the subject of Basque marine presence in these areas, we recall that, as Carlos Clavería states, a college of Basque pilots has existed in Cádiz since time immemorial.

With time, Basque participation in the wars between the English and the French in the 14th and 15th centuries became obvious. During the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453), the Basques signed up with French ships, thanks to the different treaties they had signed together.

The Basque Country’s commercial fleet became fairly strong. In that 14th century the seamen’s union grew increasingly until it established its own Consulate in Brussels, in the "Easterlings" quarter.

But another scenario and other activities call for our attention.

16. Reproduction of the cog represented in the transept of Bayonne Cathedral.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

17. Our waters guard the memory of the corsairs' adventures. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

18. During the 14th and 15th centuries, Donostia-San Sebastian was the most important commercial trading area on the Cantabrian coast and the place most frequented by the German traders from la Hansa, known as "sterlings". The name of this Donostia-San Sebastian street is a reminder of a guild or hostal which they must have had there. © Joseba Urretabizkaia