Protection, sacred and secular

Protecting the farmhouse with help from heaven

It is said that the house was a sacred family temple to the Basques, however, this religious concept of the house, wide-spread amongs ancient peoples, rapidly diluted until its disappearance during the last century. Luckily, some ethnographers, such as José Miguel de Barandiaran, were still in time to experience this concept before the Civil War, when it was still part of an organized structure of rites and beliefs, where magical Chistian elements were intertwined with abundant, more primitive references, belonging to a deeply rooted naturalist mythical universe.

Many of these customs- which still partially exist as traditional gestures, although without their past content of faith- were used for begging the sky or other invisible forces to protect their house and the family which lived therein.

Who or what was a threat to the life of the farmhouse? There were many real or imaginary dangers of which the Gipuzkoan farmers were afraid. Worst of all was lightning, which often started fires in the Province; but also jealousy or ill will on the part of their neighbours, who could put some kind of curse upon the family and bring them or their cattle down illness. The presence of foreigners, witches, mythological beings called lamiak, and other fantastic beings also had to be plotted against by means of the appropiate rites to avoid the peace of the home being disturbed.

The houses were protected by hanging signs and objects around them which acted as protective amulets. Many of these were of Christian origin, such as the anagrams “IHS” which could often be seen on the arches of farmhouses dating from the early 16th century, and the cross, which appears in different variations over the ages: stone crosses on the ridge of the roof, small blessed wooden crosses, nailed to the doors, crosses painted in lime around the windows and, lastly, crosses carved into the beams and lintels.

Some plants and bushes also had the power of protection, especially laurel, whose branches accompanied the farmhouse from the moment when the roof was finished. On the other hand, thistles were considered to be particularly good at driving away evil spirits and it was believed that white thorn had the power of averting lightning.

United against fire

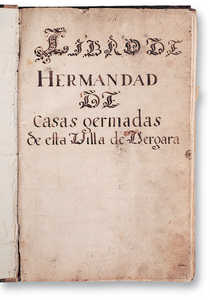

Magical rites were not enough to stop lightning or a simple domestic accident from repeatedly causing fire and the total destruction of farmhouses. To alleviate these disasters, voluntary associations for providing mutual insurance were created long ago in which each of the member associates undertook to contribute a certain amount of money to cover the cost of reconstructing the affected building. One of the earliest of these was that founded by a group of property-holding neighbours in Azpeitia in 1541 by means of an “Escritura de Concordia en razón de los incendios de casas y sus reparos”-“Bill of Agreement for dealing with house fires and their repair” and another, which lasted for many years and of which even some Biscayan farmers became members, was the “Hernandad de Casas Germadas”, created in Bergara in 1657, which had more than three hundred associated farmhouses in the mid-18th century.

This system brought in important amounts of money and meant that the rebuilding of a destroyed farmhouse could be carried out with relative ease. In order to avoid fraud, the person receiving the compensation was obliged to rebuild a complete farmhouse of normal size and quality, and not make reparis or build a simple shack.

The owners of rented farmhouses would normally include fire insurance payments in the rent, meaning that they were covered against any eventuality without any financial effort on their part.

Fireproof farmhouses

Much more efficient than the conspiracies and prayers against fire were some original architectural solutions adopted as from the 16th century onwards to protect Gipuzkoan farmhouses.

One of the most widespread measures dating from that period was that of creating an interior wall to isolate the bedrooms from the rest of the house, and especially from the usual places where fire would break out, such as kitchen and the stable.The cowshed in particular, which was lit by oil candles and where livestock moved around great piles of dry fern, was a deathly combination. The fire wall separating the bedrooms was built with no combustible elements and even the door through it, which was locked with a key at night, wasn’t built in wood, but in sheets of riveted iron.

As from the late 17th century, the increasing use of stone in the construcion of farmhouses made it more difficult for fire to spread through their interior, especially as a solid trasversal partition was often built as a fire wall.

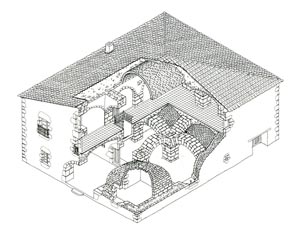

Gipuzkoan farmhouses were becoming safer, but they certainly never went as far in their adoption of prevention measures as that of Larrañaga in Urrestilla. This hundred-year-old house burned down in February 1711 and its owner, the stonemason Martín de Abaria, wanted to make sure that the same thing would never happen again, so he put a master from the province of Santander, Lázaro de Laincera, in charge of a confusing project in which the supporting pillars, the floors and the roofs were made in stone. The result was a building unique to its kind, with twenty-one interior vaults of different types, but which faithfully reproduce the functions and external image of a normal famhouse.