History of the farmhouse

It is said that one midsummer’s day, a brave hero called “San Martintxiki” succeded in robbing a handful of wheat seeds from the lords of the mountain, the basajaunak giants, and that shortly afterwards, he was able to spy on them whilst they were talking amongst themselves and find out what time of the year was best for sowing them.

This old legend, which Jose Miguel de Barandiaran listened to during his childhood in Ataun, tells of the fantastic adventures which permited the Basques to discover the secrets of agriculture, previously only known to the creatures and divinities of the forest.

This theft of secrets from the ancient gods is how the starving Gipuzkoan shepherds and harvesters started ther transformation into farmers, setting out on a long cultural cycle which lasted until the industrial Revolution.

The cycle of agricultural civilization was a long process during which the ecological landscape of the territory adapted itself step-by-step to the slow rythm of farm work, with the appearence of farming communities, who gradually made their houses into a sophisticated work tool, as well as the main expression of their own cultural identity.

The door to that mythical era, in which San Martintxiki and the basajaunak lived, closed, long ago, never to open again. Unfortunately, we can’t peep through the keyhole to see how the primitive Gipuzkoan peasants managed to work the virgin soil of its valleys, making it difficult for us to imagine how they organized themselves or in what conditions they lived: what their houses were like, where they were located and how they started storing the first harvests.

Although the problem may seem serious, it is not really too bad if we consider that our main interest is to approach the history of the farmhouse in the strictest sense , without getting lost along the magical paths of legend. The mythical origin of the farmhouse is one thing, and its true history as a specific type of European regional house another, and we are lucky in that we don’t have to navigate the shadows of time nor go back to the neolithic revolution to trace its first true steps; but can find them by simply looking at the centuries towards the end of the Middle Ages. The information sources available today, which are still exasperatingly limited, cover all the stages of life in the Gipuzkoan country house. Although it is true that the firs steps have fuzzy borders which need more research, it is still possible to state that the history of the farmhouse has two key moments which can be considered as the true starting point of its biography. Each of these moments makes reference to one of the possible definitions of the term caserio; a name of ambiguous meaning, which is synonymous with both the ecenomic institution as well as the building which housed it.

Should the farmhouse be interpreted in its widest economic sense, that is, as the basic cell of family production in mountain agricultural societies, then we can confirm that it is an institution of mediaeval origin which took shape between the 12th and 13th centuries.

If, on the other hand, we consider the farmhouse as a certain kind of building, that is, an architectural model with a specific identity, then we would be talking about a kind of modern regional farmhouse with a maximun age of half a millenium; an age not surpassed by any of the rural buildings existing today in Gipuzkoa.

One peculiarity which singles out Basque farmhouses is the fact that they all have their own names, which are recognized by the authorities and neighbours, and which normally never change throughout history. This menas that they can be easily identified, but it sometimes creates misunderstandings such as crediting the building with the same age as the name of the economic unit to have been settled on the same site over the ages, which was almost always prior to the farmhouse itself. However, when a farmer is asked about the age of the house in which he lives, he unfailingly tries to go back to the origin of the site, ignoring the antiquity or medernity of the builing’s architecture.

Farmworkers and farmhouses in the Middle Ages

Farmworkers were the largest social class in Gipuzkoa during the late Middle Ages but they were considered as second rate to the lords ang rich men. They were made up of a wide group of families who lived in fear of threats from rural proprietors and suffered abuse from a nucleus of local aristocrats, who were relatively few in number, but who had sufficient resources to pay armed men to forcefully make themselves respected.

The farmers were not a homogenous group, but were divided into three graded categories. The most favoured of these were the fijosdalgo or free proprietors, owners who had full right to the land they cultivated and who had no tax obligations to the King nor to any other particular lord.

Below this group came the majority subgroup- which in many regions comprised two-thirds of the peasant population- made up by the so-called king’s labradores horros or pecheros.These men were generically free, and autonomously managed their farmhouses, but couldn’t leave them without substituting themselves with another member of their own family, as the land they worked belonged to the crown and they were required to pay a series of pechos or taxes with the result of their work, such as martiniega ( a tribute paid on Saint Martin’s Day), infurcion (rent paid for the land), fonsado (war tribute) and servicios (a special tax for cattle).

The monarch’s distance meant that this situation of dependence gradually became more tolerable but, in exchange, they became extremely vulnerable quarries for the local lords.

During the most virulent period of the late mediaeval crisis, at the end of the 14th century, many farmers took refuge in the jusisdictional protection of the boroughs against violence from the lords, even offering to pay for this protection, as did the neighbours from Uzarraga, who became taxpayers to Bergara (1391), those of Ataun, Beasain, Zaldibia, Gainza, Itsasondo, Legorreta, Alzaga, Arama and Lazkano to Villafranca (1399)and those of Udala, Garagarza, Gesalibar and Uribarri to Arrasate (1405). However, in the 16th century, when peace came to the fields of Gipuzkoa, the old pecheros prospered until reaching the same level as free farmers, proudly and unashamedly exhibitng the antiquity of their rural farms, and awarding themselves the pompus title of “señores de su casa y solar” (lords of their house and land).

The lowest step on the mediaeval social ladder was occupied by the collazos: peasants with no personal freedom who, amongst get married without permission from the lord they worked for.

The worst fear of the fijosdalgo and pechero farmers wat that of being collectively subjugated by someone of nobility or an important Relative who would humiliate them and treat them as vassals, as the Lazcano had done with the inhabitants of Areria until 1461. However, the danger which most frequently became reality was another, that of armed attacks on individual farmhouses, due to the fact that they were often far from one another, or desparramados, according to the inhabitants of Mendaro in 1346. A few years earlier, in 1320, the Oiartzun council had clearly described the situation to Alfonso XI, indicating that:

“sus casas de morada eran apartadas las unas de las otras y non eran poblados de so uno (...) e tan aina no se podian acorrer los uno a los otros para ser defender de ellos de los males, e tuertos, e robos que les facian”.

(“their houses were far apart from each other and were only inhabited by one family (...) meaning that it wasn’t easy to defend each other against crooks, injustice and robberies”.)

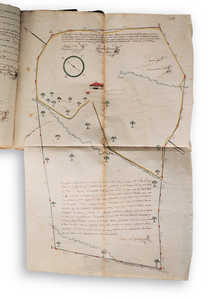

Similar stories of division were told by the farmers of Zumaia (1347) and Usurbil (1409), thereby confirming thas this was the general structure of the whole territory, However, it would seem that this is a somewhat exaggerated observation, caused by the insecurity of the times and the desire to found boroughs under the shelter of royal privileges. In the places where it has been possible to reconstruct, even although only partially, the map or rural population in the 14th century –in Antzuola, Bergara and some areas of Goiherri- it is obvious that there was a settlement clustered around the middle and bottom of the hillside- with high saturation of the highest yielding plots. Likewise, it has been proved that farmhouses which were isolated at extreme altitudes were pratcially unknown and that, in comparison, areas or villages were taking shape as the basic structure of the farmworker’s social organization.

From the wooden shack to houses of cal y canto (stone masonry)

Houses of Gipuzkoan peasants in the Middle Ages didn’t look anything like the farmhouses being built at the end of the 15th century. Although these no longer exist, we know that they were fragile and uncomfortable shacks. They were wooden huts, that weren’t built with trunks, but with a frame made with posts to which vertical planks were fixed on the outside to make the four walls.

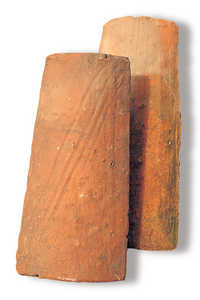

These mediaeval huts were much smaller than present-day farmhouses, but there was room inside them for the animals and storing hay, as well as a living area for the family. However, the press house, granaries, pigsty and sheepfolds were located in separate buildings. Even at that time, the roof of these constructions was made from ridged tile, at least on the main house.

The first stone farmhouses in Gipuzkoa were built during the 15the century and brought admiration and envy from their neighbours. Only the richest farmers could permit themselves the luxury of building a house “de cal y canto”, paying a team of stonemasons who dug out and worked the stone. Oakwood was, ont he other had, cheap and availabe. Even for the poorest peasants, because they could cut down all the trees they needed for their house free-of-charge in the public forests belonging to the council.

Although we find increasingly more information about new rubblework houses during the last decade of the 15th century, the decisive birth of the Gipuzkoan farmhouse as we know it took place in the first half of the 16th century. The feeling of security and prosperity which was spreading through the fields and the possibility of making a fortune after the reign of the so-called Catholic Kings, both in America and in Andalucia, allowed the farmworkers to live more comfortably and make optimistic plans for the furute.There was no longer any danger of attacks or robbery by the nobles, and peasant families’ hearts became filled with the priority of living in a decent and lasting home, instead of the ramshackle huts which had given them shelter until then.

There was a real explosion of new farmhouses in stone and wood or, more often, using mixed techniquies in which both materials were combined in ingenious solutions.

Several hundred of the farmhouses built in the 16th century ara still standing and the most surprising thing about them, apart from their old age, is the high quality of their carpentry and stonework; often greatly superior to the houses built hundreds of demanding mentality. Inside, they are spacious and have clearly defined functions. Although there are many local varieties, they all have two stories: the lower for the family and their domestic animals and de upper for storing the harvest.

Cellars were also used for storing the wheat harvest, which was well protected in huge wooden chests called “trojes”. Wheat was a unit of wealth which, on the western side of the territoy, in the Deba valley, is why some of the richer farmers adopted the idea of builiding tall wooden granaries in front of their houses and decorating them with beautiful carvings and geometrical figures. They knwe that the bigger and more elegant the granary, the more respect they would enjoy in the region. Today the only granary still standing is the magnificient example of the Agarre farmhouse in Bergara, but there are several clues which point to many others having disappeared from the 17th century onwards.

The 17th century was probably the happiest period in th life of Gipuzkoan farmhouses. Land ownership was acceptably distributed and the farmers could enjoy the fruit of their work in an atmosphere of economic expansion and optimism. It is certain that the climate, type of soil and difficult orograpy of the territory were not the most appropiate for cultivating cereal, but the continous effort of the whole family succeeded in wresting the bread they needed to live from the soil. The sale of cider, chestnuts, meat, cow horns and leather helped them to complete their low incomes, and local markets were well supplied with wheat from Navarre or Castilia to cover the natural deficit of the region.

The mediaeval panorama changed radically in less than a century and, where frightened and down-trodden peasants had previously lived, proud farmers were now flowering who competed to see who cuold build the largest farmhouse, the most beautiful arches and most artistic wooden carvings. The wind of the Renaissance was blowing strongly throuth the narrow valleys of Gipuzkoa.

Farmhouses and the arrival of corn

The most active sectors in the Gipuzkoan economy fell into a deep crisis at the end of the 17th century. Ports along the coast saw the collapse of the international trade of Castilian wheat and wool and the blockade of the Terranova fisheries, causing a serious decline in shipbuilding, for which it had previously been outstanding in Europe. In the interior valleys, the Associations of craftsmen and blacksmiths who worked in the boroughs were faced with serious difficulties for placing their products on the traditional markets of Andalucia and the Atlantic coast. The defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588) in which many Gipuzkoan boats and sailors disappeared, and the spreading of a virulent outbreak of the plague in 1598 made many people fear a return to the Middle Ages they thought were well behind them.

Assailed by problems which it couldn’t resolve, the Gipuzkoan society soon returned to the countryside. The rich started looking towards the farmhouse as the only safe investment in which they could place their capital without risking bankruptcy and the poor started looking to the countryside for work and the means of subsistence denied to them by other areas.

But traditional crops were not sufficient to feed all the mouths in the Province and the best farmland was already so saturated with people that it was impossible to fit in any new settler families. Just when anxiety was starting to spread, a new plant from America appeared almost miraculously which was to completely change the life and customs of the Basque farmers: corn.

This new cereal acclimatized quickly and produced triple the volume in grain than wheat, and it adapted perfectly to the humid and sloping land which had previously been used for the ears of Mediterranean wheat.

Important landowners saw this exotic crop as an opportunity for making high profits from many of their outlying plots, where they built new farmhouses for renting out. For their part, the less important farmers, who had previously seemed doomed to emigration, got out their long-pronged ploughing forks and set to work tilling the virgin land which had, until then, been left to forests, meadows and gorse bushes. To compensate the cattle for the disappearence of natural pastures, they planted fields of turnips and icreased the amount of time which the cows and oxen were kept in the stables.

Nobody got rich by cultivating corn, but the new seed from America gave more families a decent living than ever before in the Gipuzkoan countryside.While the rest of the local economy was collapsing, farmhouses were not only coming out of the crisis, but they were growing in number, population and productive capacity.However, in the mid-term, they were unable to avoid the general market decline, and lack of stimulating demand caused local farmhouses to close in on themselves, strengthening themselves as a network of very coservative family ecenomies, which were completely self-supporting.

The cycle of corn expansion lasted until half-way through the 18th century. During this period the most comfortably-off families in Gipuzkoa showed continuous interest for accumulating as many farmhouses as possible and linking them to their line of heirs by means of entailed estates.

Until then there had been a scrupuloulsy applied principle that only one single family would live in each farmhouse, but, thinking in terms of getting the highest yield from their land, the larger landowners discovered that it was much more profitable to rent each house to several tenant farmers. The demand for farmhouses was so urgent that they could always find several candidates willing to get married and establish themselves, even in conditions of relative overcrowding.

Wheat had not yet disappeared. Its flour was still highly appreciated and it was easily turned into hard cash at the market. For this reason the owners always demanded that the farmers pay their rent in wheat fanegas. So, an absurd crop-splitting regime was established in the territoy of Gipuzkoa. The farmers had to sow two harvests at a time: one of corn to knead into “talo” dough to make the cornbread they ate, and another of wheat to meet their obligations to the church and entailed estates. It was only in the mid-20th century, with the disappearance of church offerings and the generalized access of “baserritarras” (local farmers) to land ownership, that the nonsensical effort of trying to plant Mediterranean wheat on the Cantabrian coast was abandoned.

Expansion and decline of the modern farmhouse

In the Gipuzkoan farmhouses of the 18th century, men and women worked sideby-side at the hardest agricultural work, and two-family farmhouses and tens of arms ready to dig and reap.The production per agricultural ecenomic unit was high but, in comparison, the yield per person was very low and the land was pushed to exhaustion. To increase harvests they even went to preparing the ground with lime from stones cooked in crafted ovens, but the abusive and indiscriminate use of this method burned some of the best plots and made them temporarily sterile.

In the decades towards the end of the century, nobody in Gipuzkoa could hide the fact that their land was producing less each year. However, the number of mouthes waiting to be fed increased continuously. The solution adopted at the beginning of the 19th century to alleviate the lack of food was to found new farmhouses by breaking up all the available land, even that of poor quality which was recovered from the land kept for pasture and from common mountain lands.

The invasion of Frech troops in 1795 and that of the Napoleonic Armies in 1807 made thing easier, because it meant high expenditure for the Gipuzkoan town councils and that tey had to sell some of the municipal land to pay off their debts.This is how the large landowners managed to get hold of new forests and fields, and even some with old hermitages, which were used for installing tenants with scarce means; often in remote and isolated areas with few possibilities of long-term success.

This wave of expansion gave good results because it was accompanied by a new change in the kinds of products cultivated. It was during this period that the lower classes added beans and potatoes to their diet, which have been developed to such an extent that today they are two of the basic ingredients in traditional Gipuzkoan gastronomy. The 19th-century land break-ups meant that the amount of corn was doubled, while the amount of wheat harvested stayed stable and other less important cereals, such as rye and oats, disappeared entirely.

Unlike the elegant stone or trellised farmhouses which had been built in the heat of the first corn boom of the 17th and 18th centuries, many of the new rural 19th century constructions were smaller and poorer looking, often simple cattle huts converted into houses.During this process the number of independent farmers in Gipuzkoa was reduced to the smallest in its history. At the beginning of the 20th century, eight out of ten farmouses were occupied by modest tenants, and in the municipalities surrounding San Sebastian the proportion was even lower, since only 10%of the “baserritarras” owned the land they laboured so wearily.

Industrialization radically changed the rules of the game with respect to the structure of ownership and exploitation of land in Gipuzkoa. The sprouting of iron and steel, textile, cement and paper industries, as well as the revitalization of gunsmiths’ workshops in the Deba valley attracted the surplus rural population and caused farmers to abandon the less productive farmhouses.Large owners were faced for the first time with the alternative of having to choose between freezing rents or seeing their fields bare of labourers to cultivate them; they soon lost interest in the agricultural land which had been collected over so many generations. The tenents were then able to buy their farmhouses at a very reasonable price – today there are scarcely 1,500 tenant farmer families in the more than 11,000 Gipuzkoan farmhouses- and they set out in the last known change of direction of the local farmhouse: the abandonment of wheat, apple trees and other low-yielding crops and their sustitution by harvest crops and plantations of fast-growing coniferous tress.

No new farmhouses have been founded during the 20th century. However, many of the old buildings have been renovated and most of them adapted to modern living conditions, sacrificing – sometimes unnecessarily – some of the elements which made the Guipucoan farmhouse one of the highest quality country houses in Europe. Presently, around 2,000 farmhouses are on the point of disappearing forever.